Design Inquiry and Repair

Year: Fall 2022

Location: Georgia Tech - Atlanta, GA

Purpose: Industrial Design Minor Capstone-ID 4833

Processes: Sketching, Design Thinking, Camera Repair

I spent a semester researching, studying, and practicing various design through repair philosophies and techniques through the lens of my grandfather’s broken Soviet film cameras. The cameras are the Zenit 14 and Zenit Automat.

This is a documentation of my inquiries, discoveries, and process. If you are interested or knowledgeable in Soviet film camera repair, please contact me. I’d love to chat!

Some Context

My maternal grandparents fled the former Soviet Union a few

years before its collapse. In the summer of 2020, my grandfather gifted me two

cameras, the Zenit Automat, and more importantly the Zenit 14, an extremely

rare camera. Only 567 were made.

The Zenit 14 was a limited pre-production concept for the Zenit Automat. They are mechanically identical, but the Zenit 14 is a fully manual camera while the Zenit Automat is only aperture priority.

The Zenit 14 was a limited pre-production concept for the Zenit Automat. They are mechanically identical, but the Zenit 14 is a fully manual camera while the Zenit Automat is only aperture priority.

Then the Zenit 14 broke

I switched to shooting with the Zenit Automat but the forced aperture priority was inconsistent and would often ruin photos. There wasn’t a single camera repair store that was willing to repair the niche Zenit camera. So now it was time for me to give it a go.My design inquiry and repair process rounds consisted of:

Readings and Exercises

→

Repair

→

Discoveries and Further Inquiries

Reading 1: Introduction to repair

Marissa Cohn’s “Lifetime Issues”: Temporal Relations and Design of Maintenance.

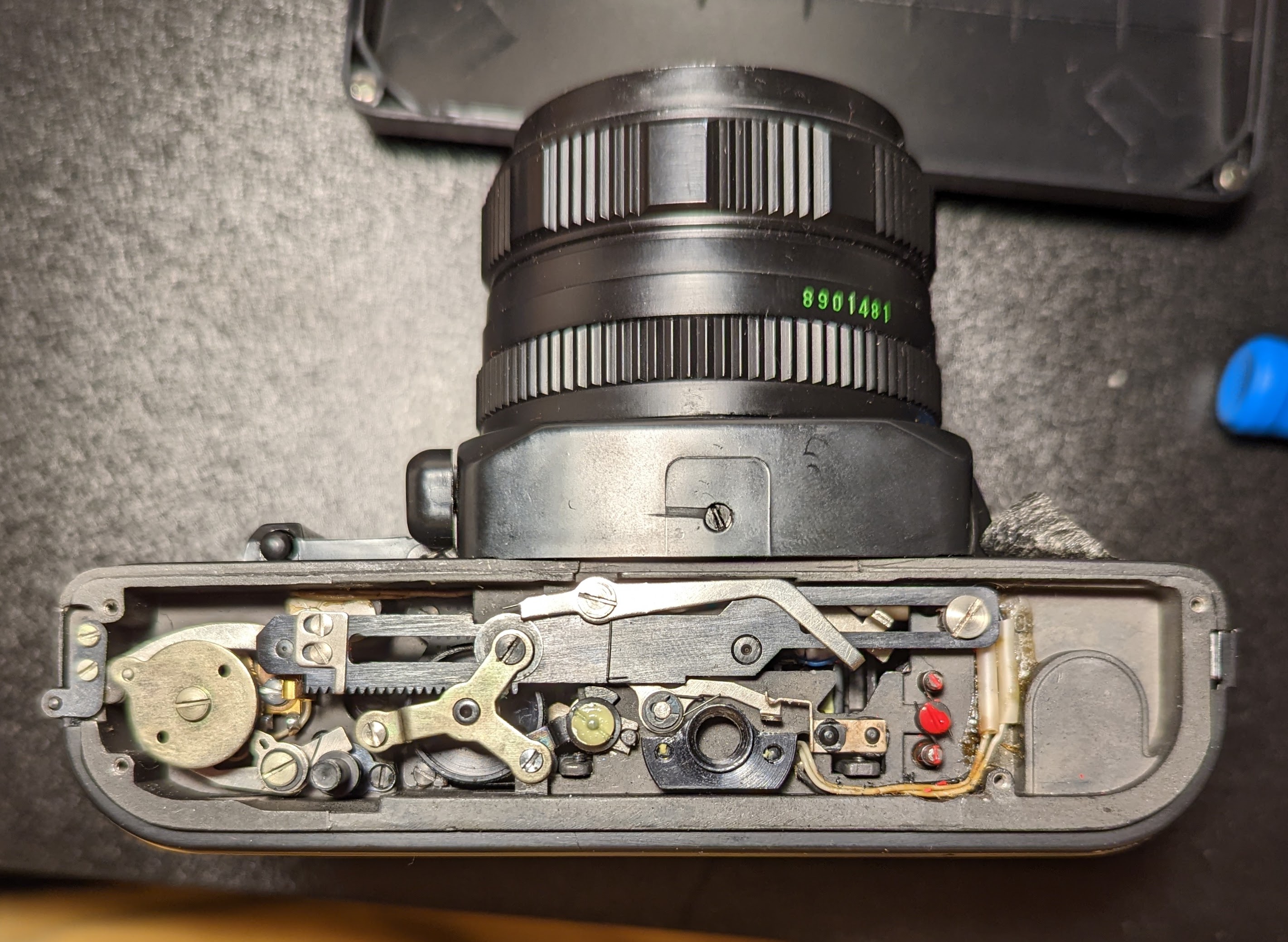

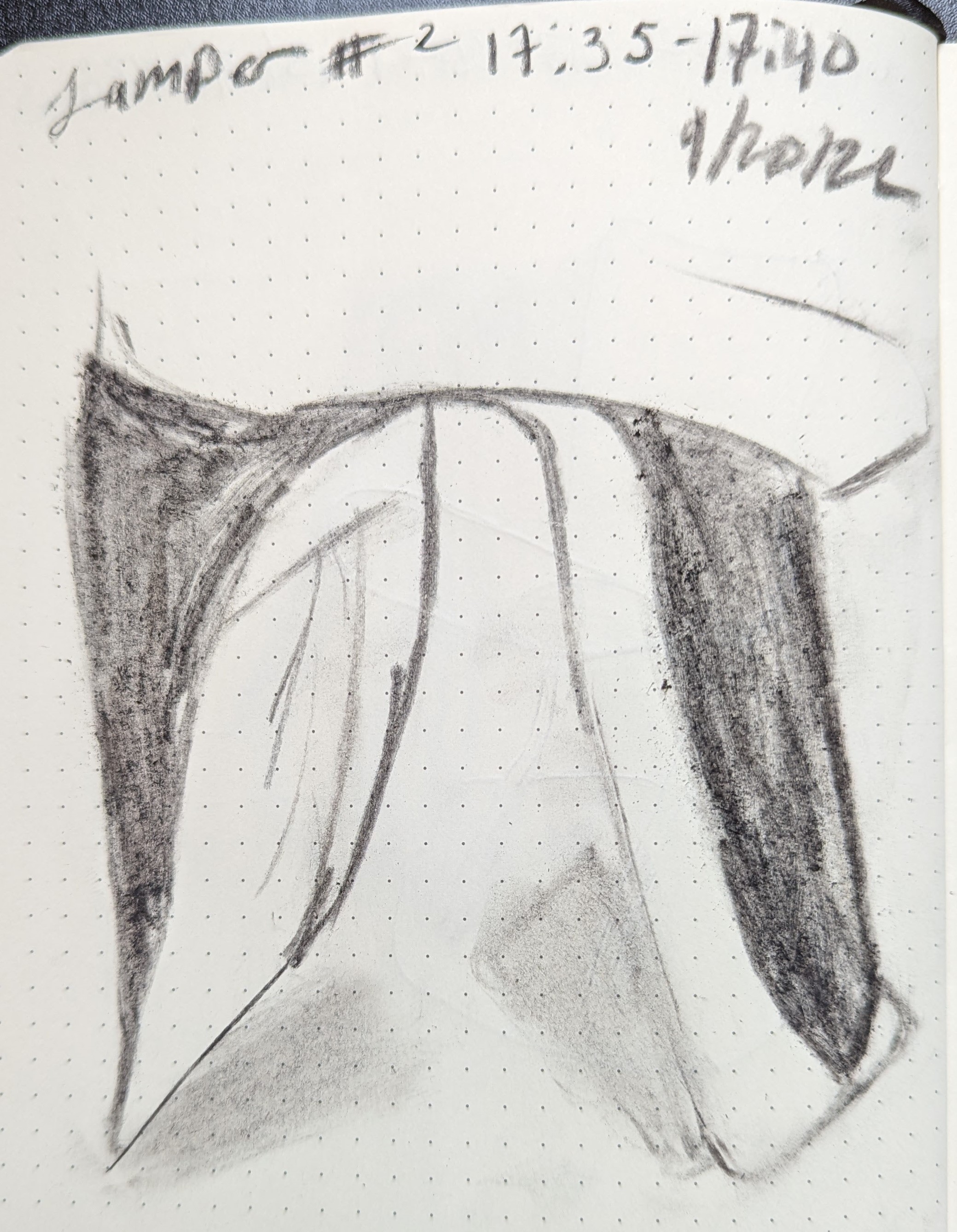

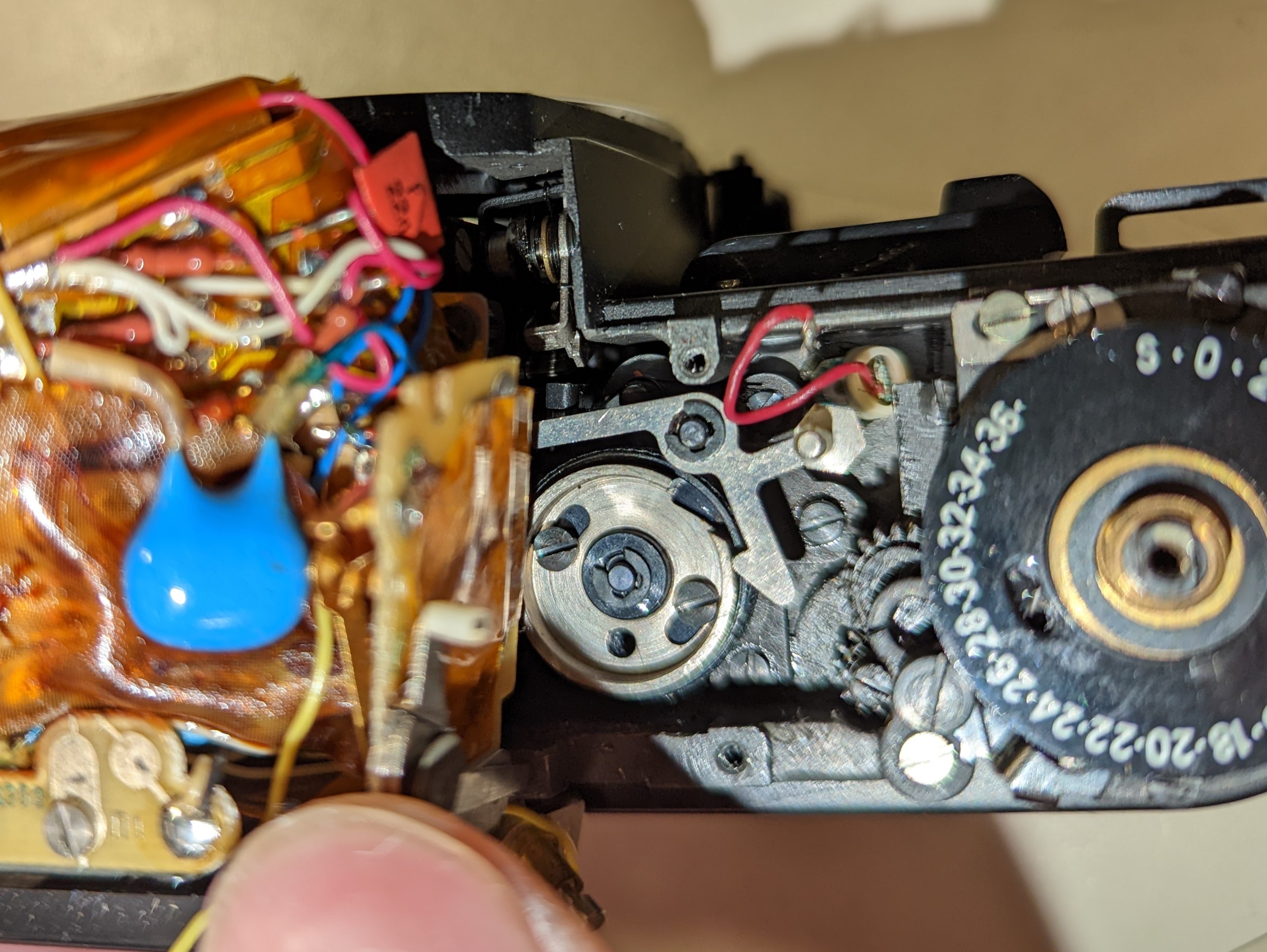

Repair 1: Exploratory teardown of the bottom plate

Discoveries and Inquiries 1: My role as the owner and operator

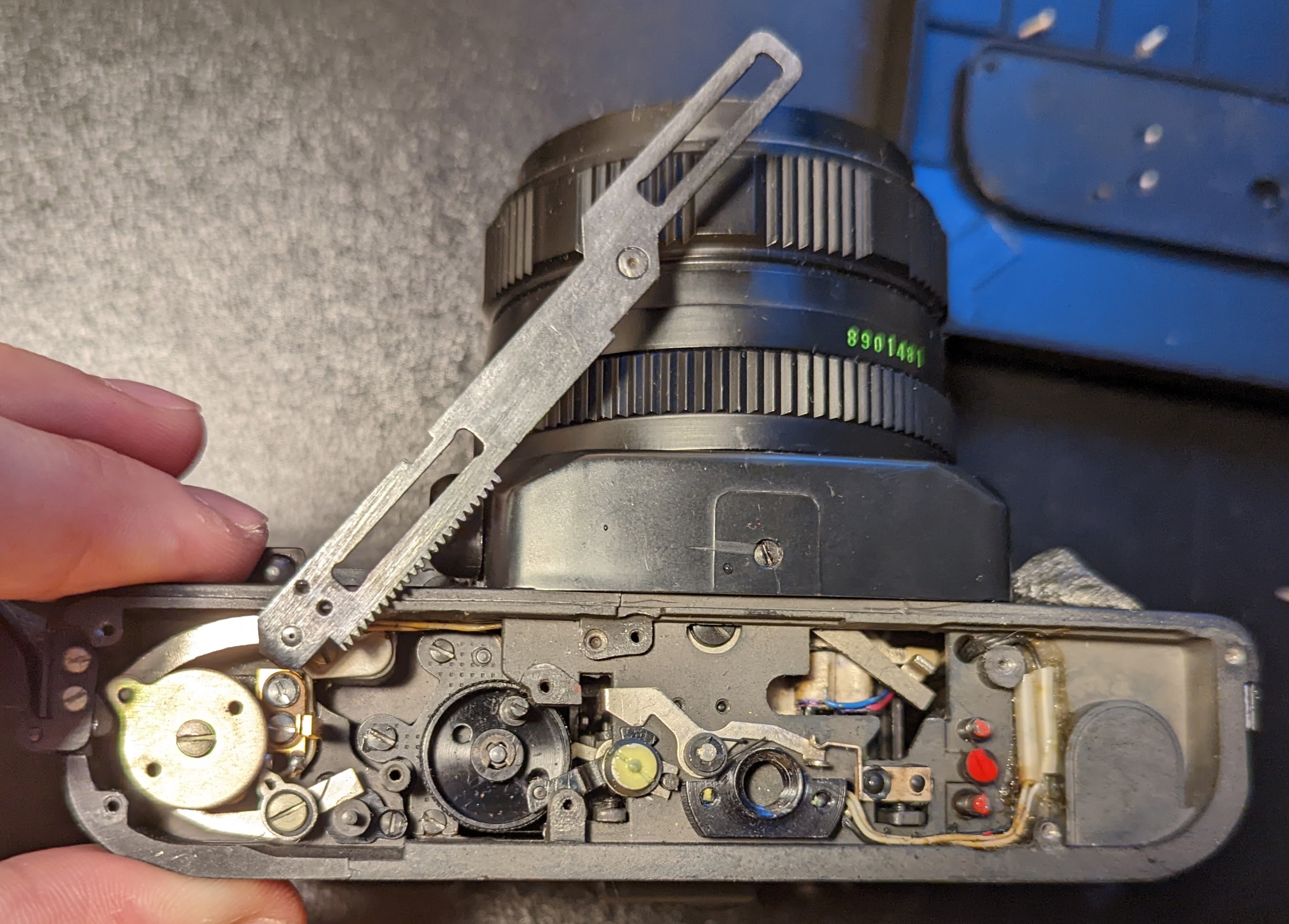

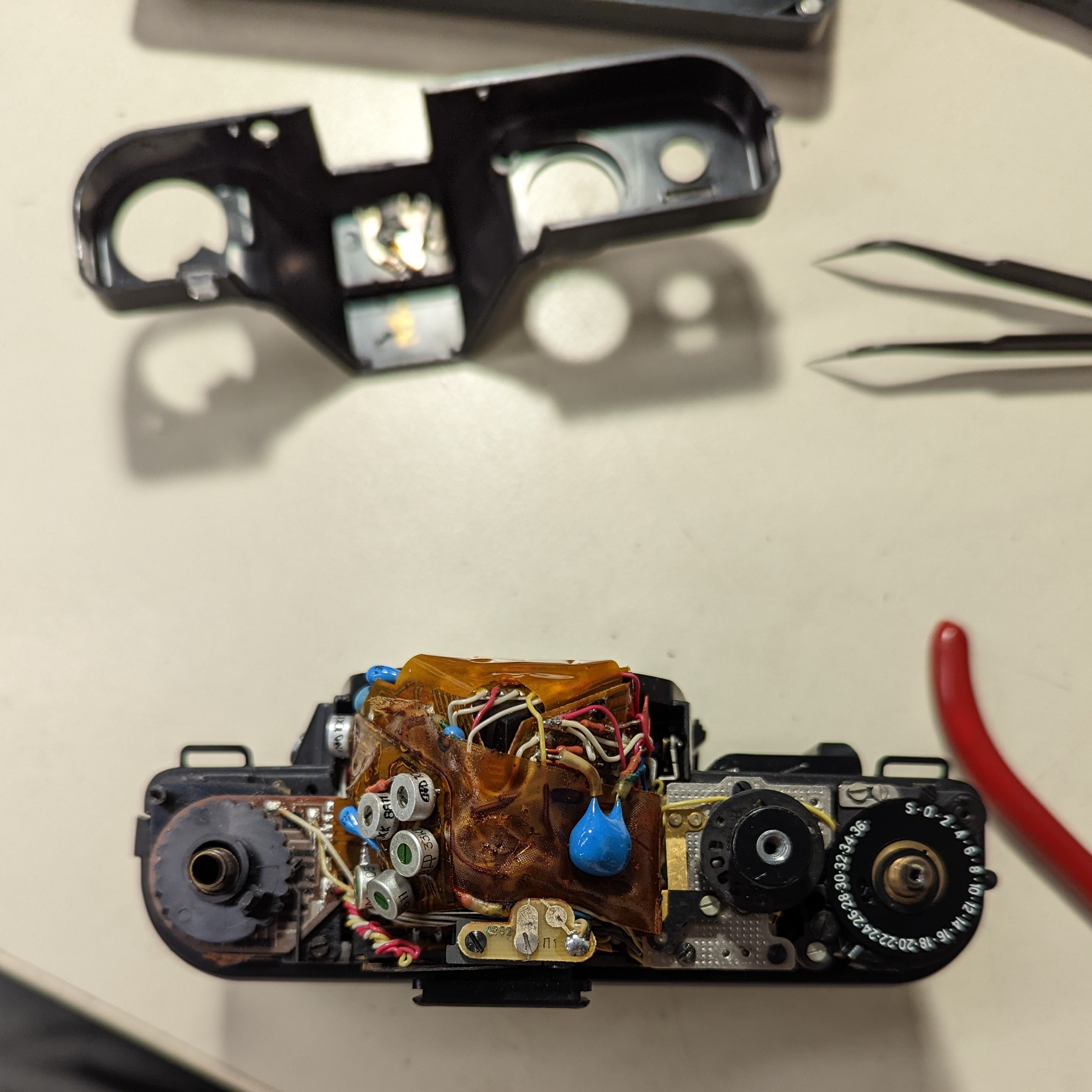

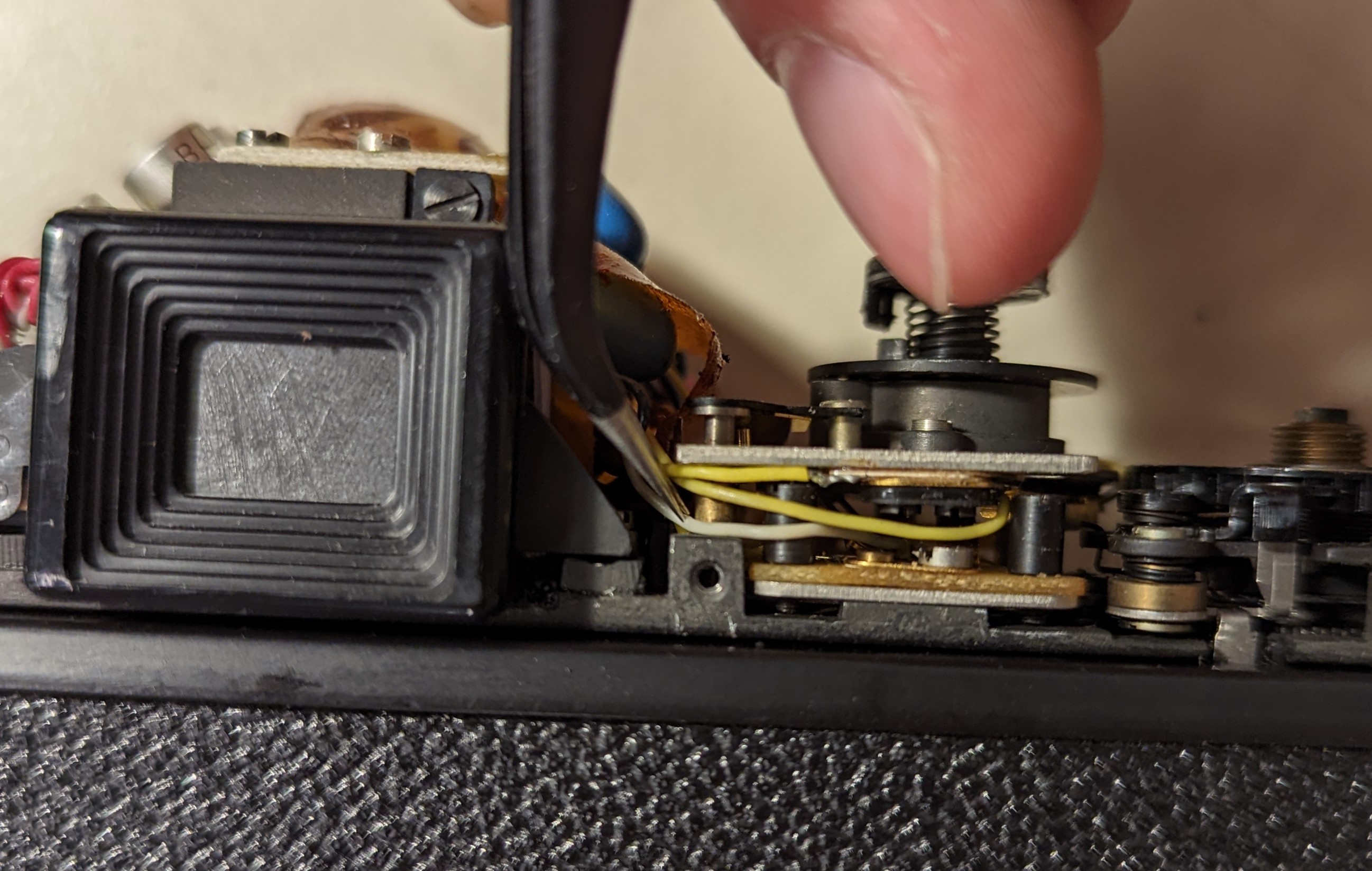

As the operator of this camera, it’s up to me to maintain and service the artifact. To see what I was working with, a camera technician recommended that I started by familiarizing myself with the mechanisms at the bottom of the camera. I took apart the mechanisms and documented my questions and discoveries.

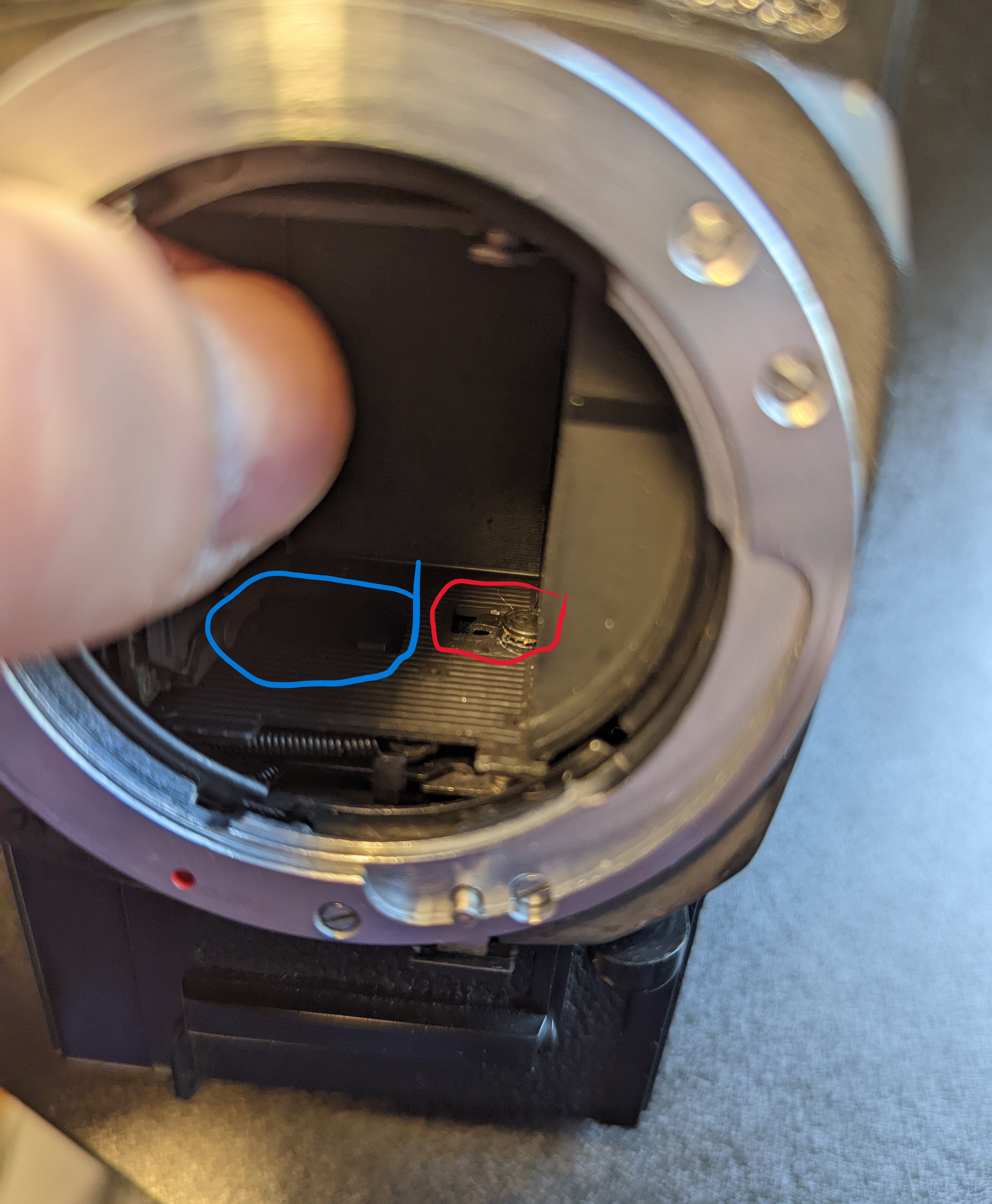

My first discovery was that there are various states of disrepair. At first glance, the camera didn’t work due to a simple misalignment of components. Only one part was obviously broken, but this didn’t seem to impact the function of the overall mechanism. However, I needed a reference for how the mechanisms interacted in a functioning camera. Unfortunately, I couldn’t ask any of the original developers of the camera, nor reference the materials found online. I was flying solo.

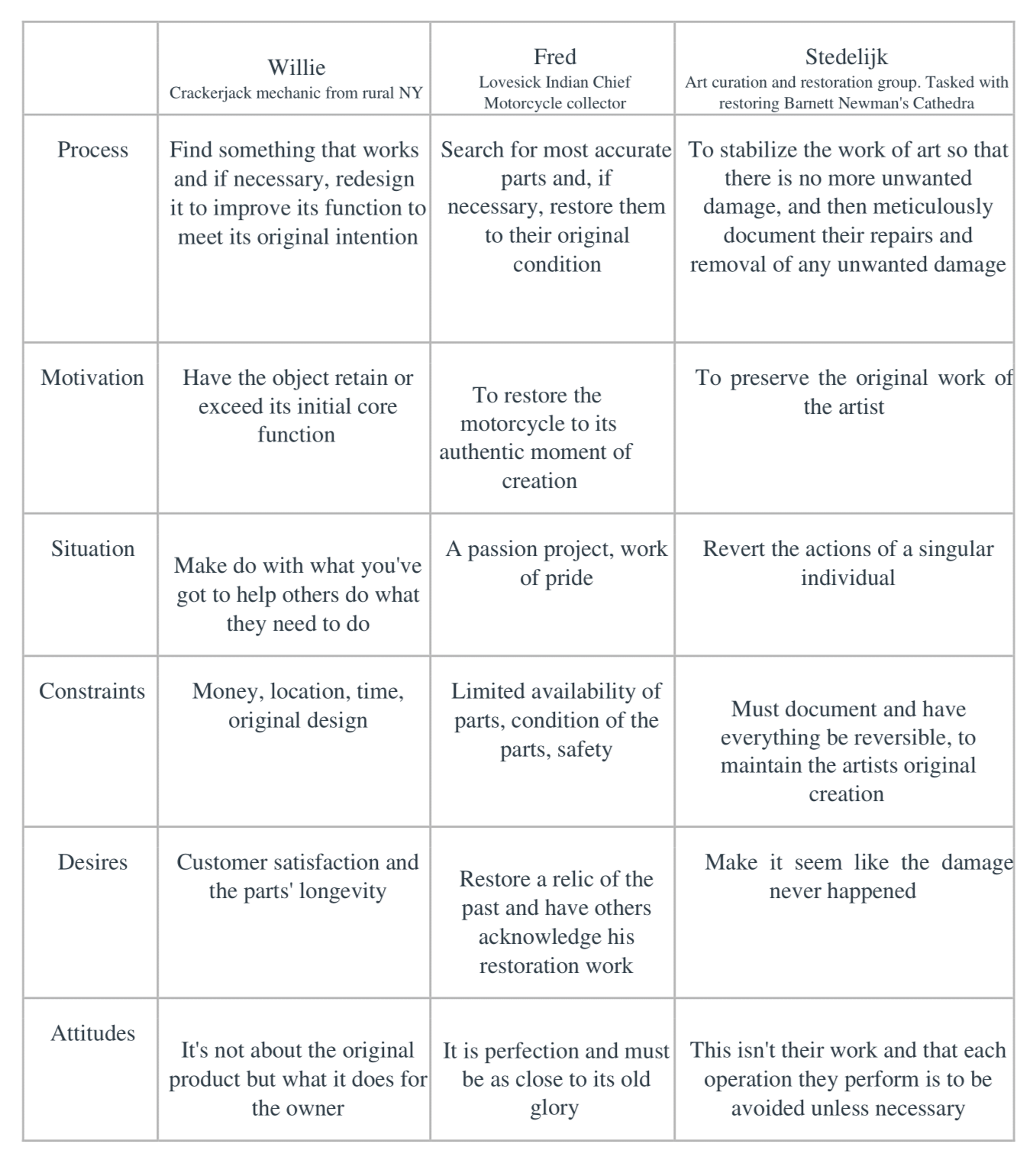

Reading 2: Learning about processes of repair

Elizabeth Spelman’s “Repair”: The impulse to Restore a Fragile World Ch. 1, 2, and 7

Repair 2: Repair of the bottom plate

Discoveries and Inquiries 2: Scope of the repair

The progress I made helped me discover that there is no fundamentally wrong approach to design or repair. My repair could be visible or invisible, traditional, exploratory, restorative, or explorative. What is imperative is the intention.

Reading 3: How to holistically understand an object

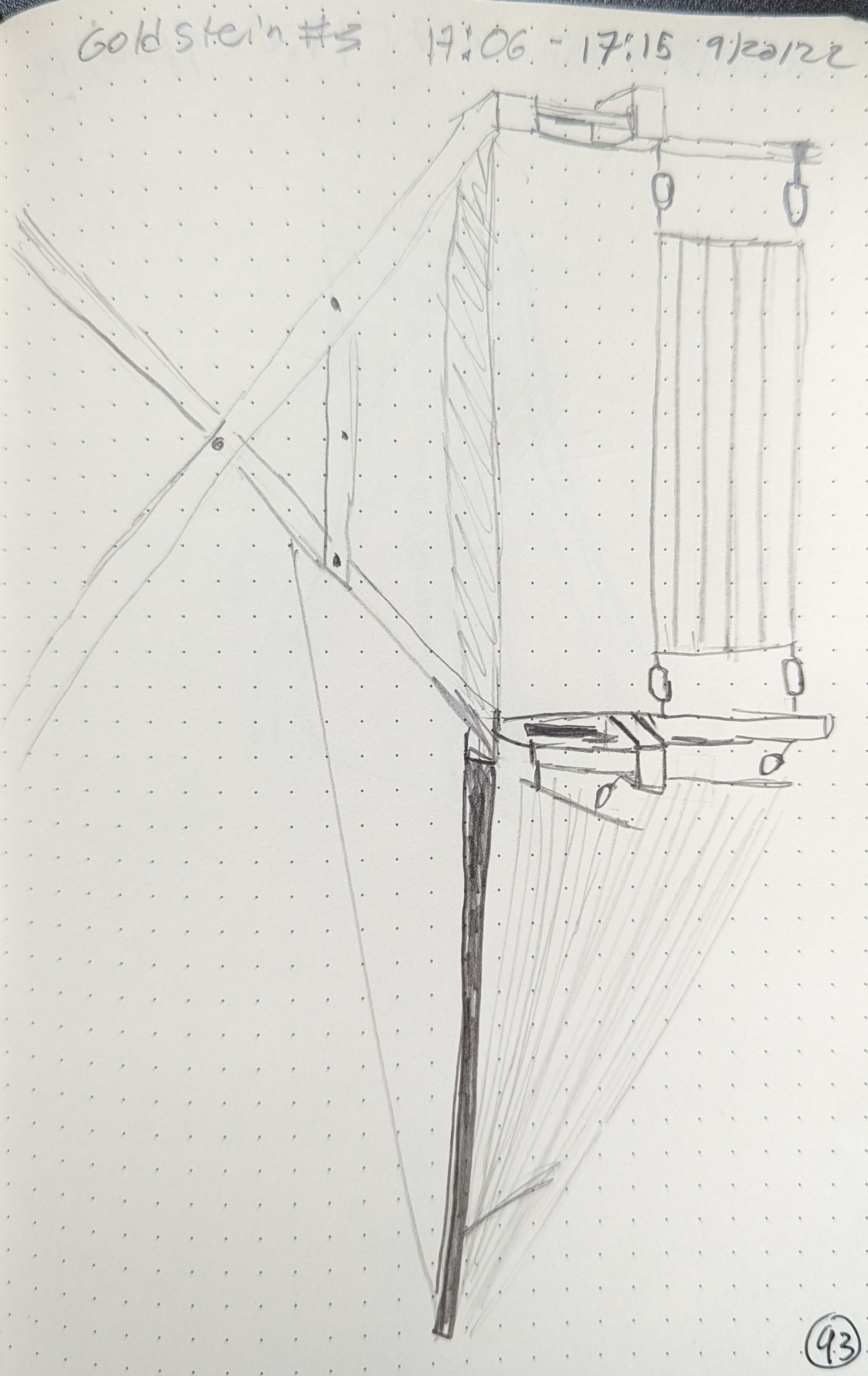

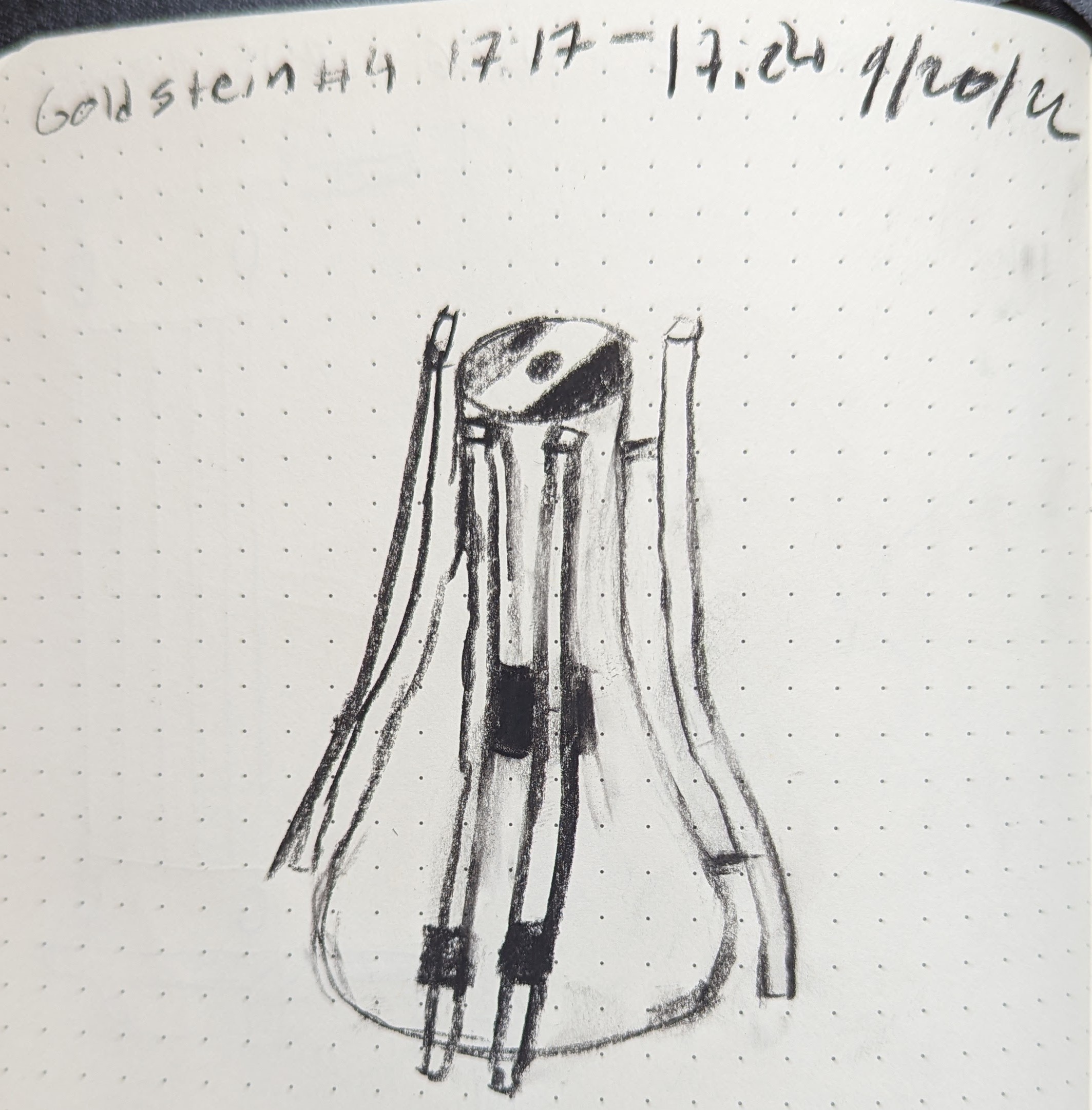

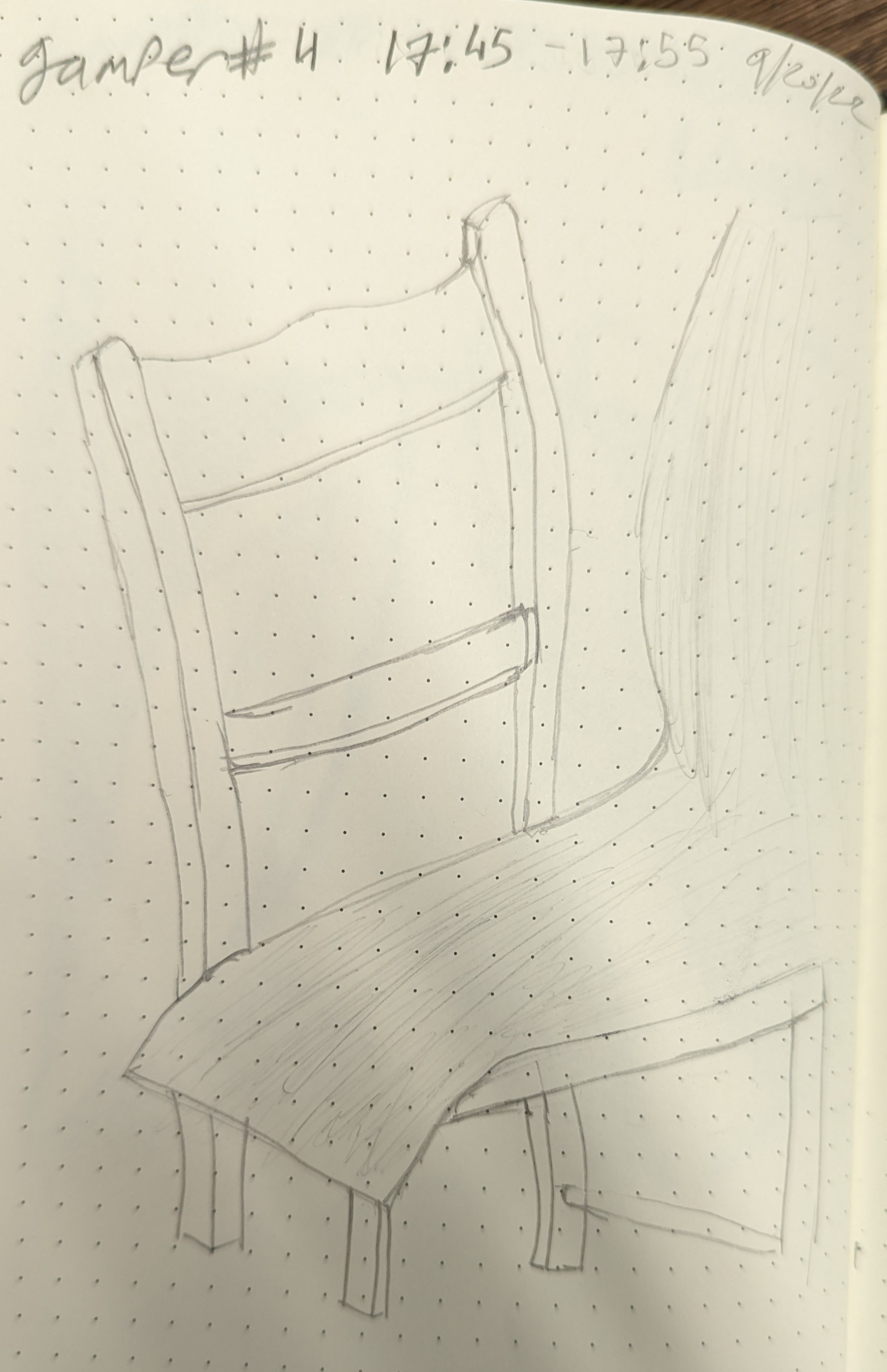

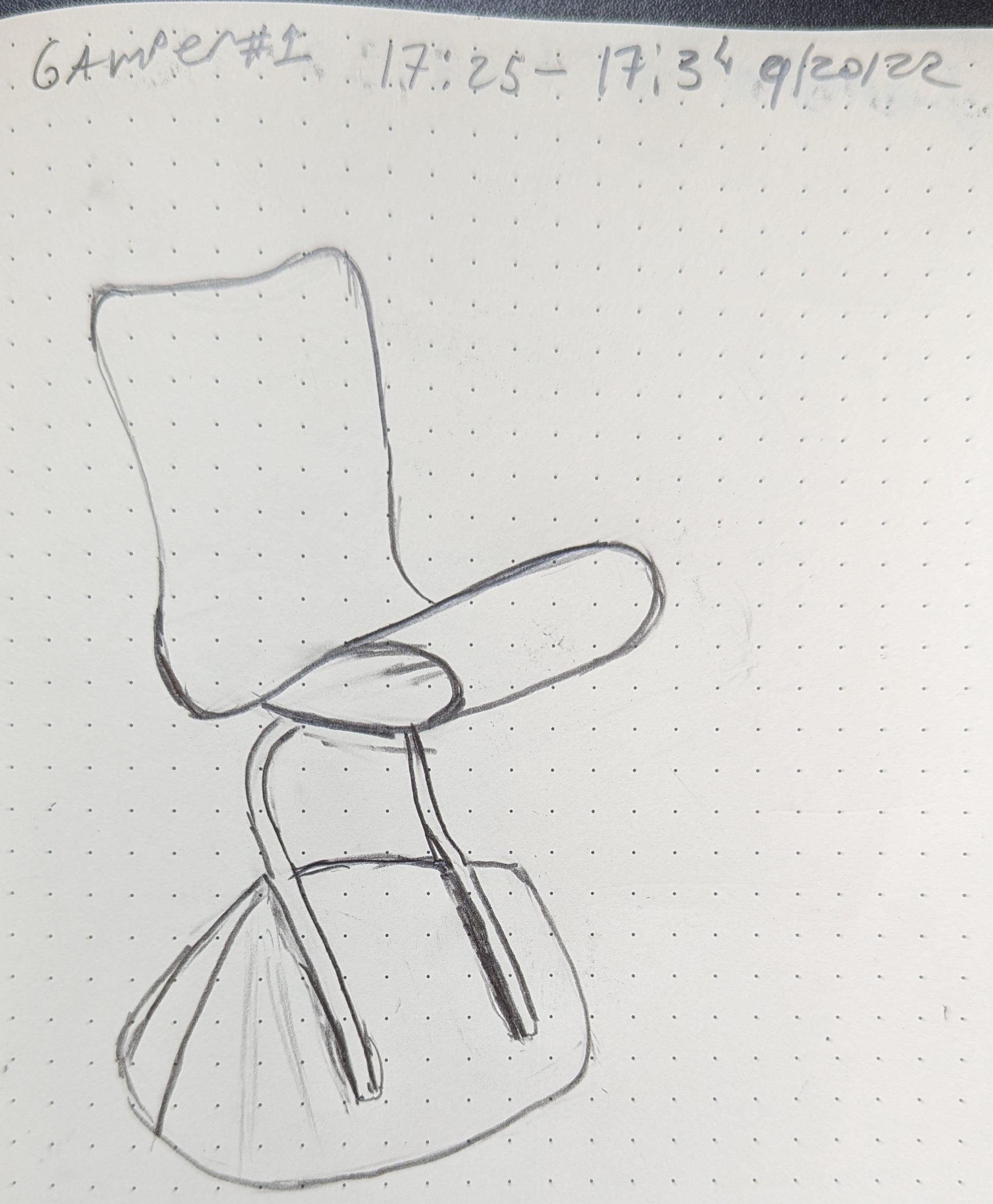

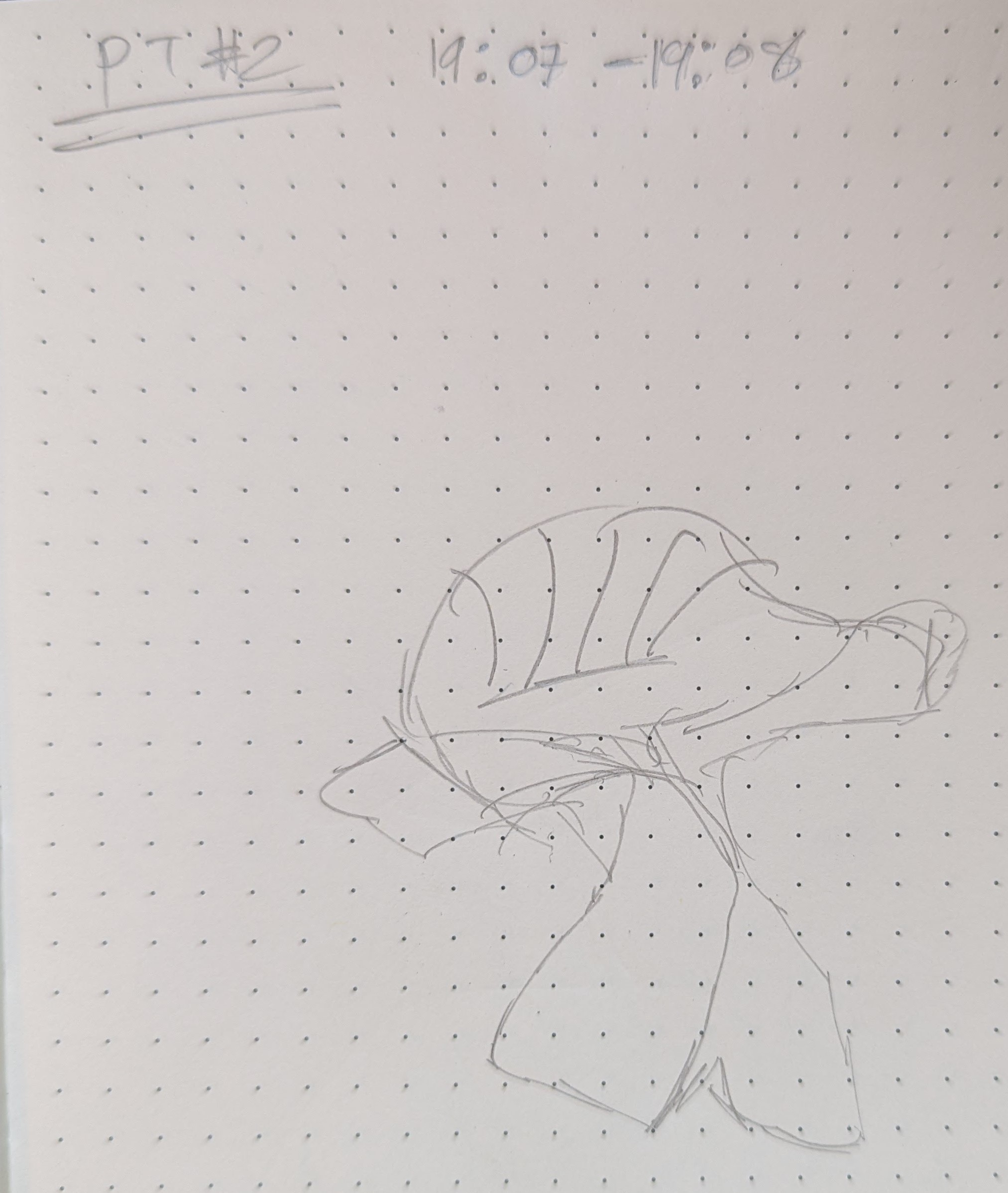

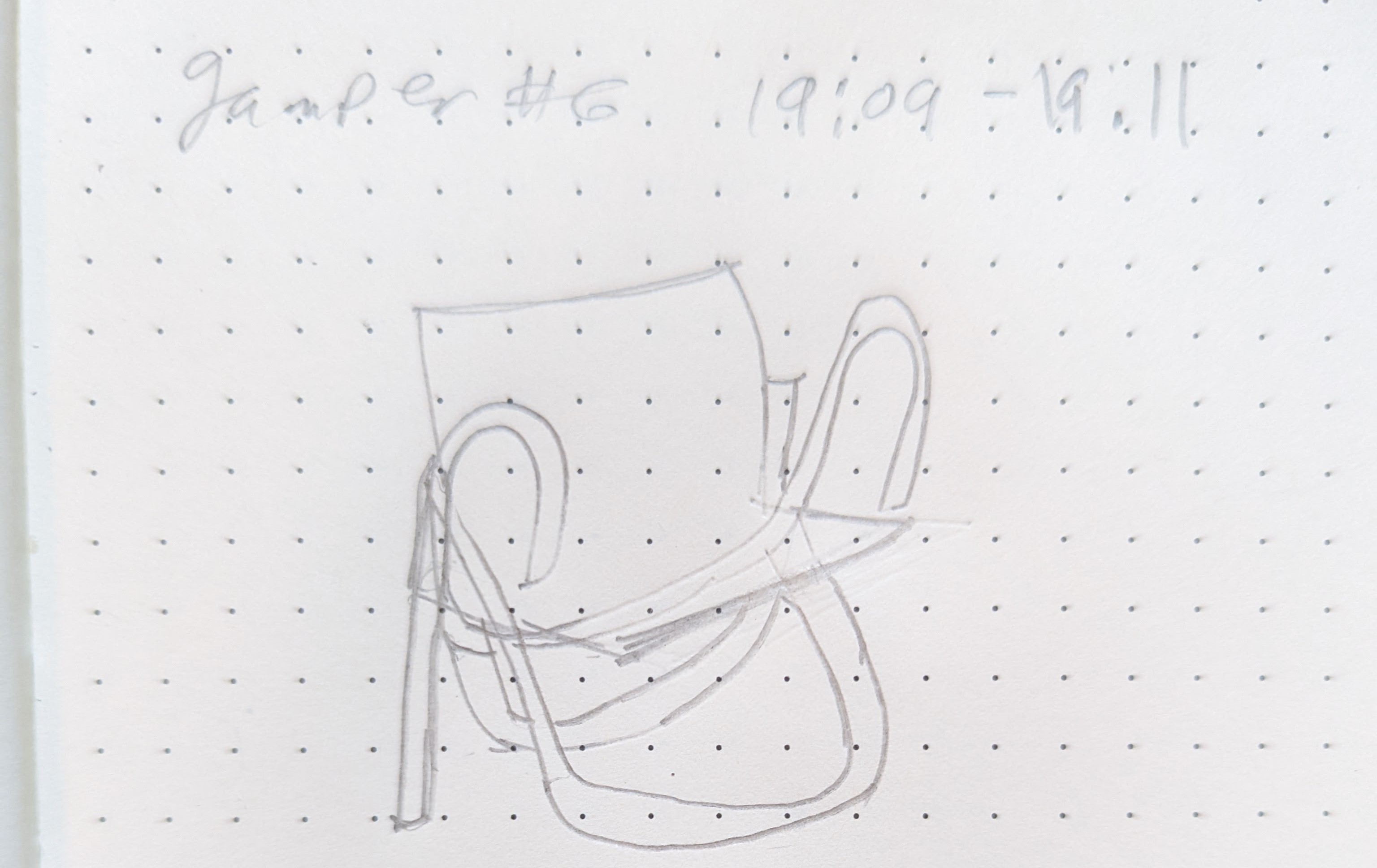

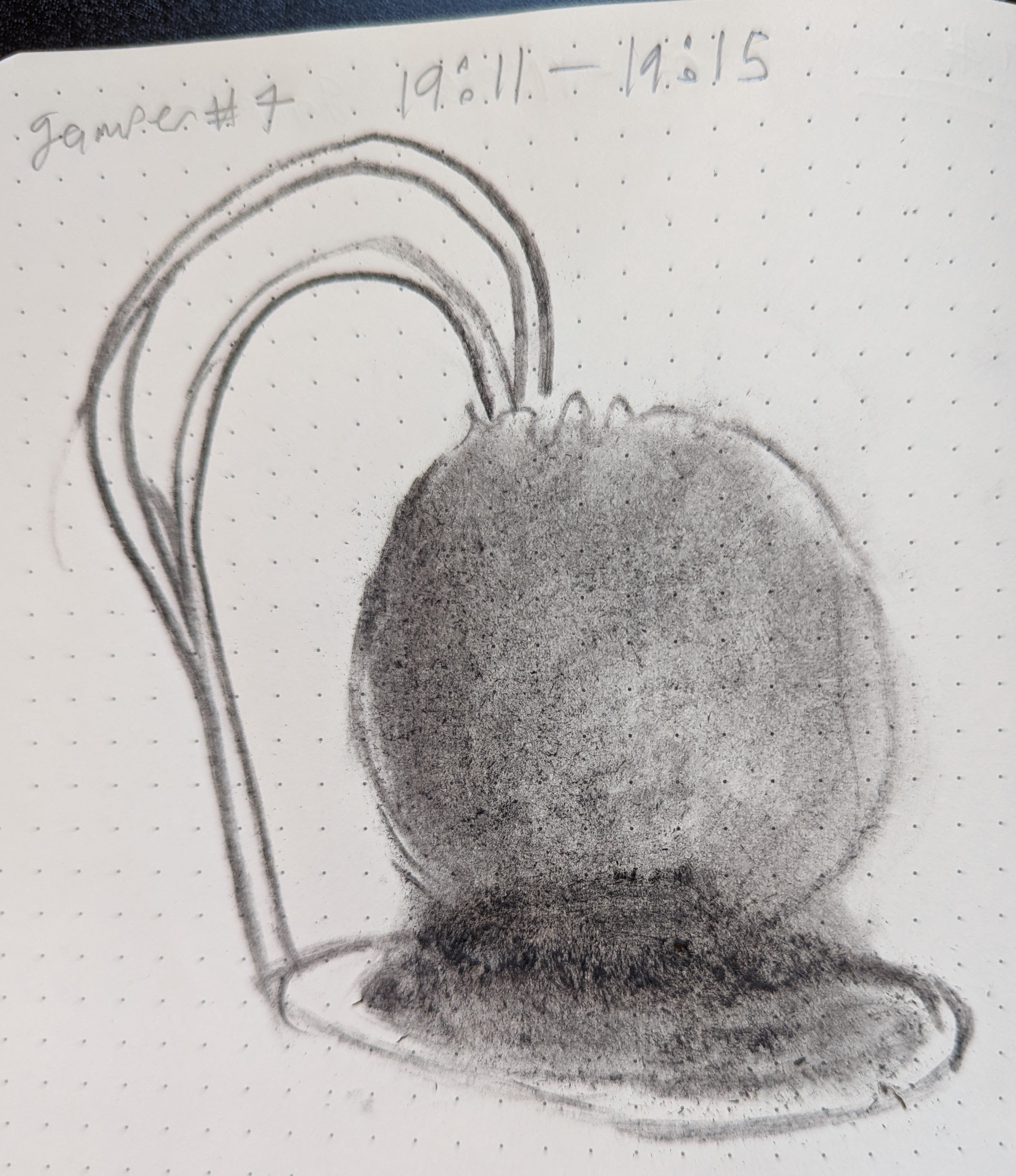

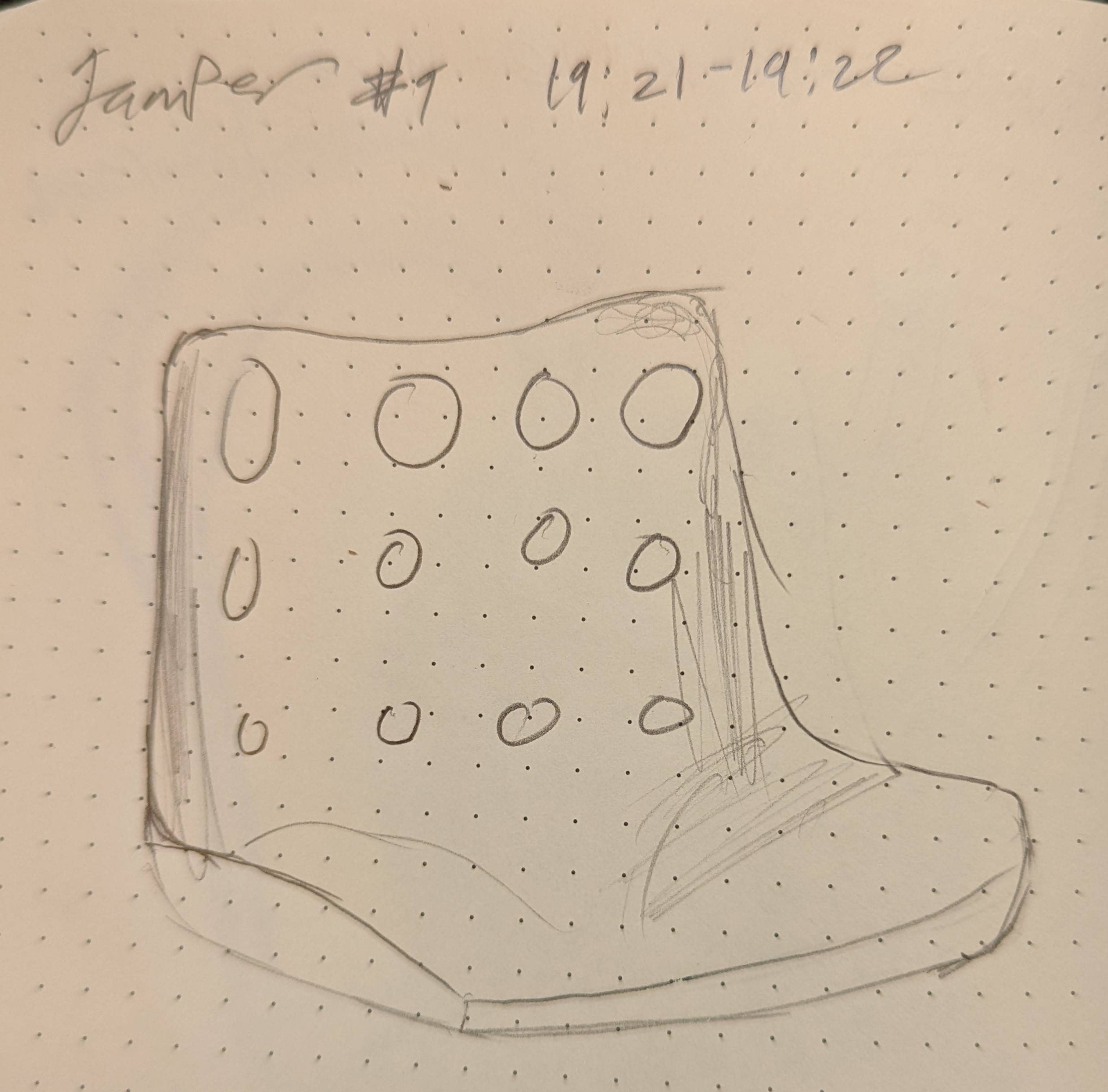

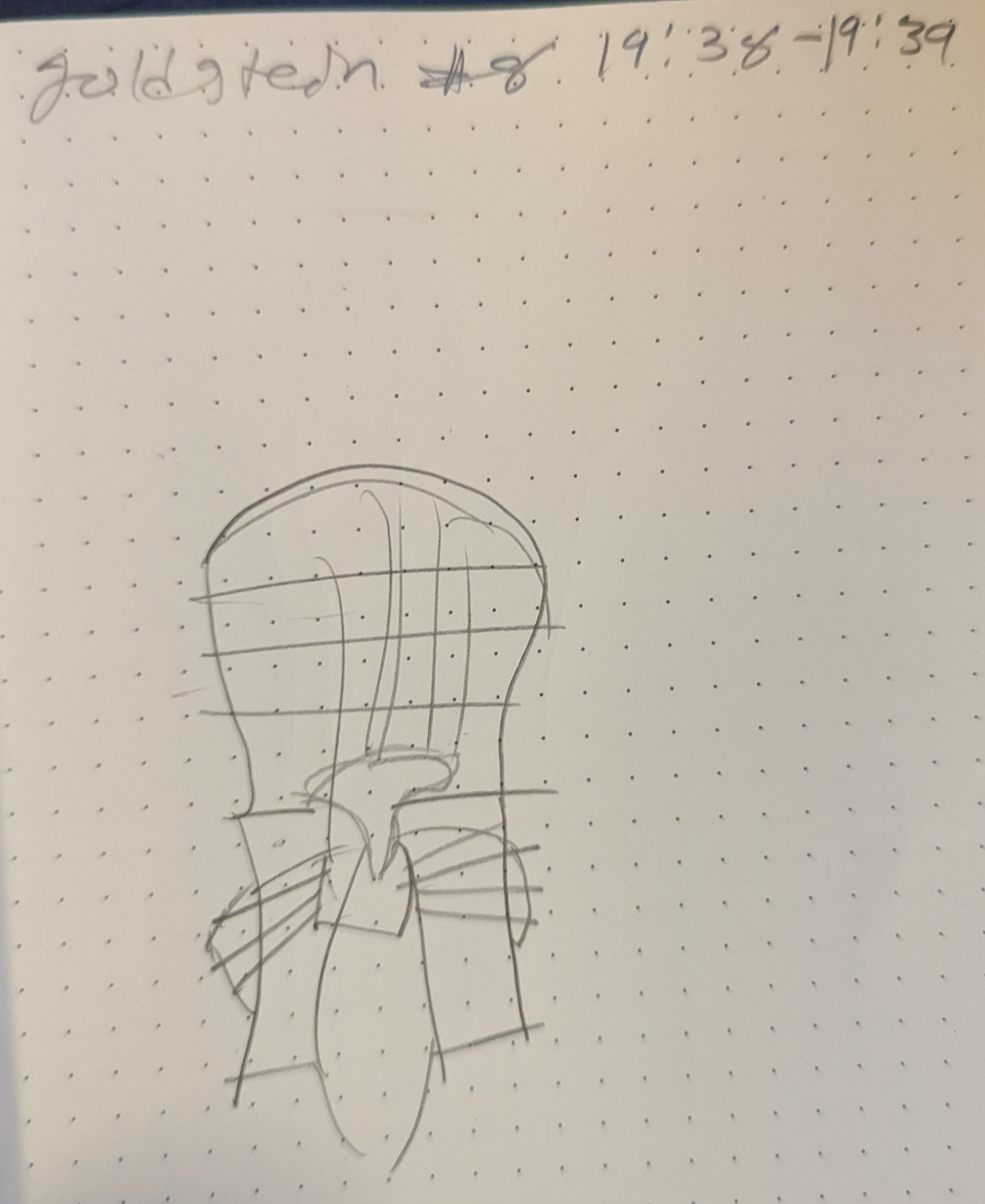

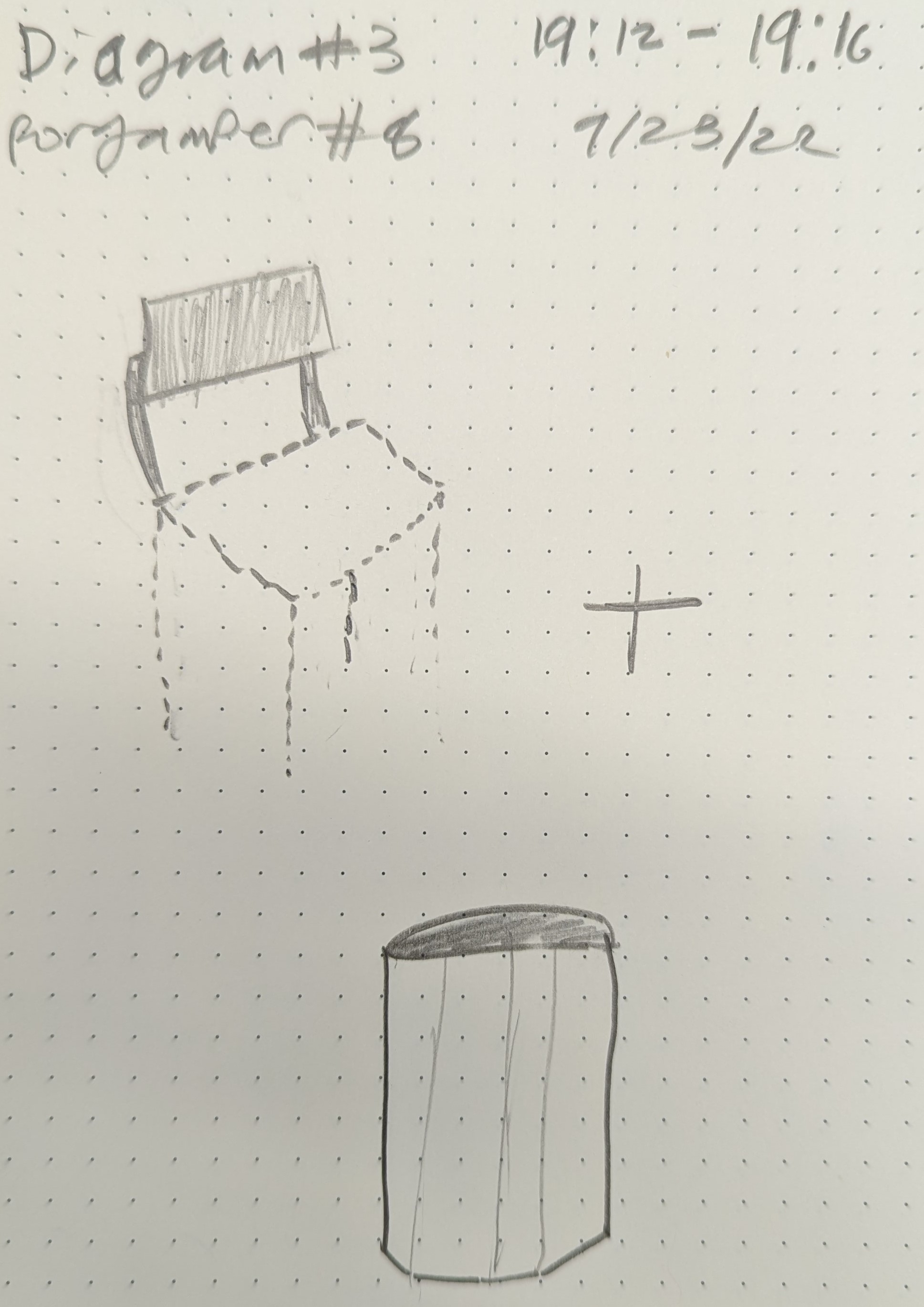

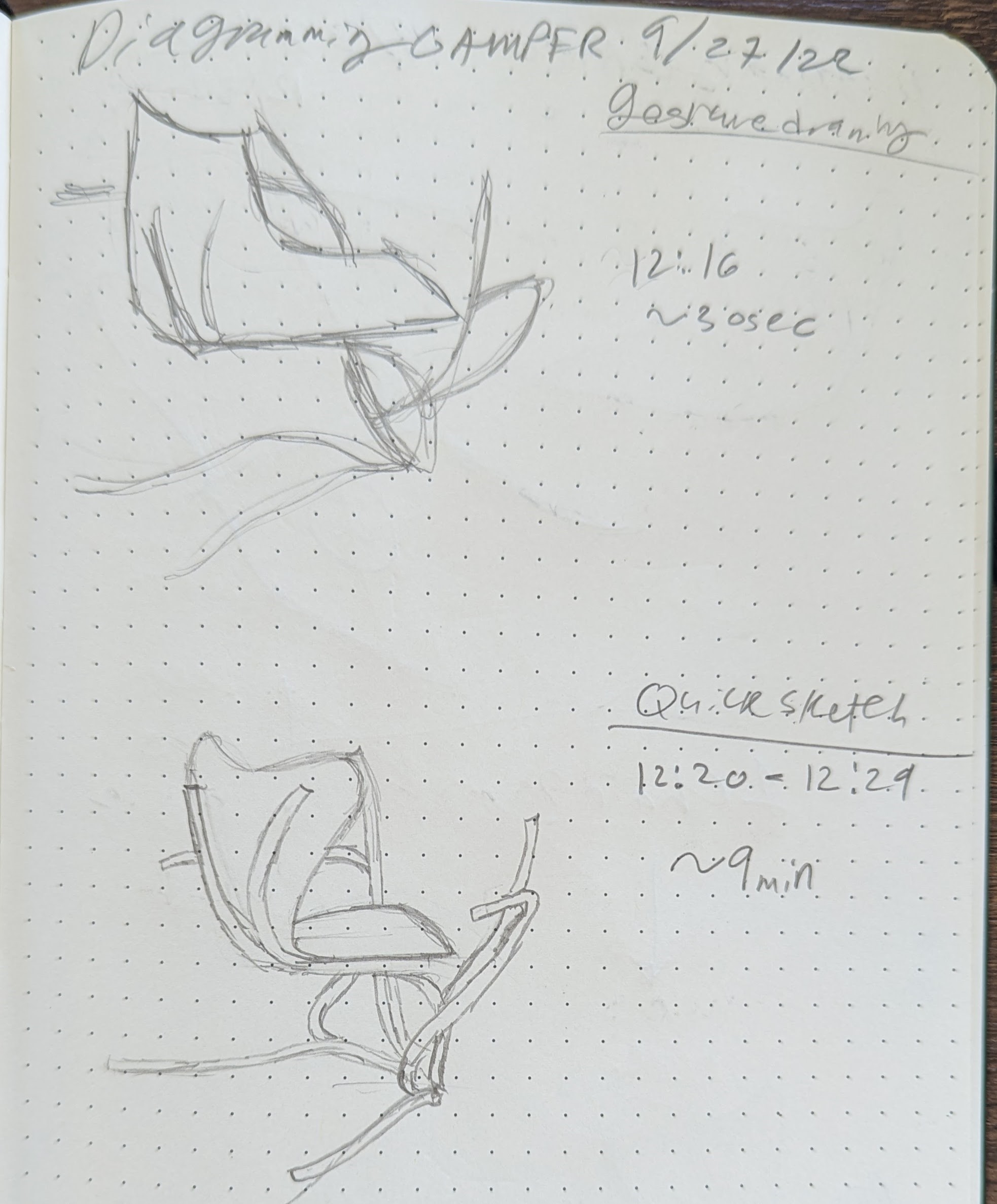

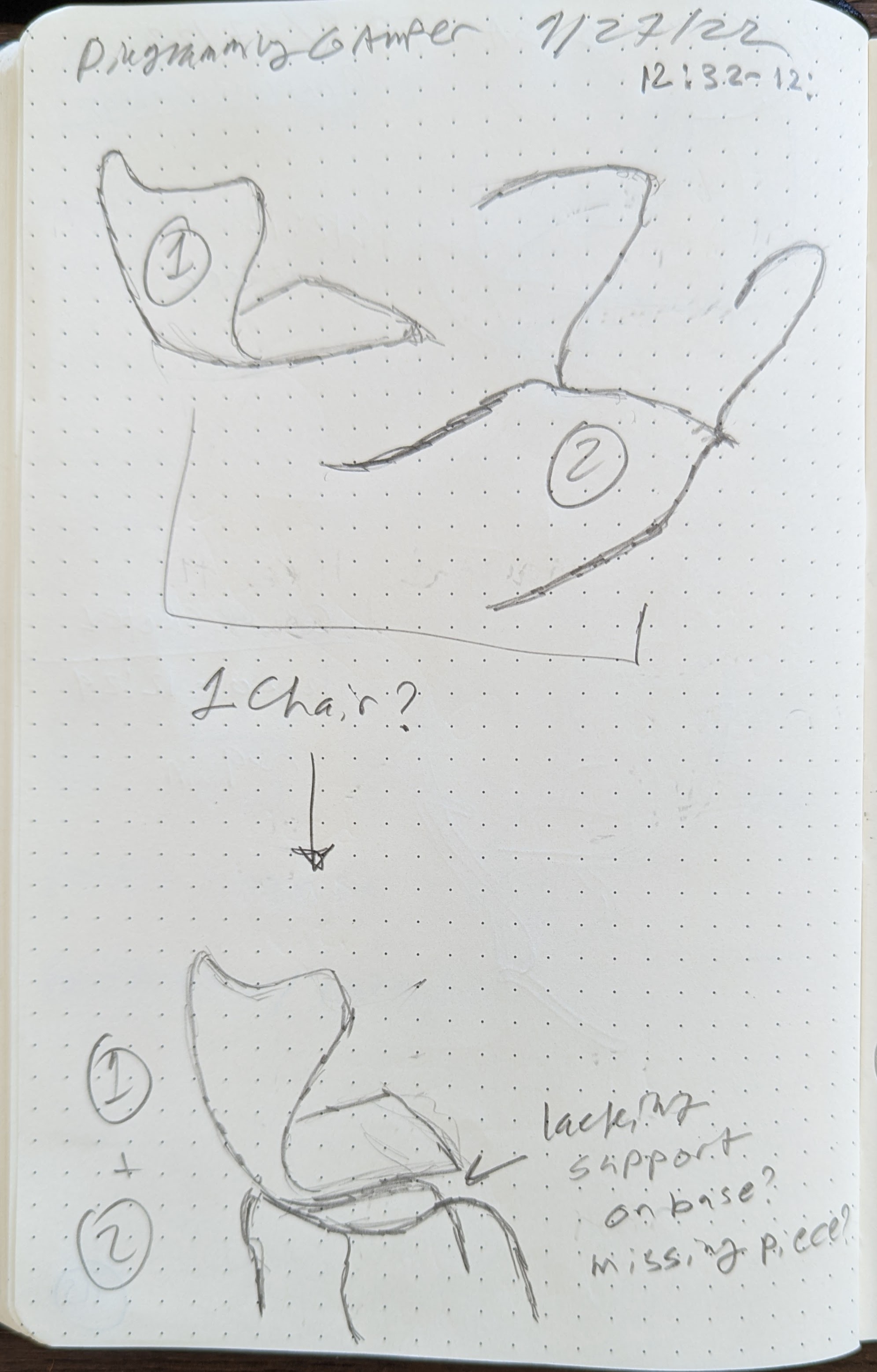

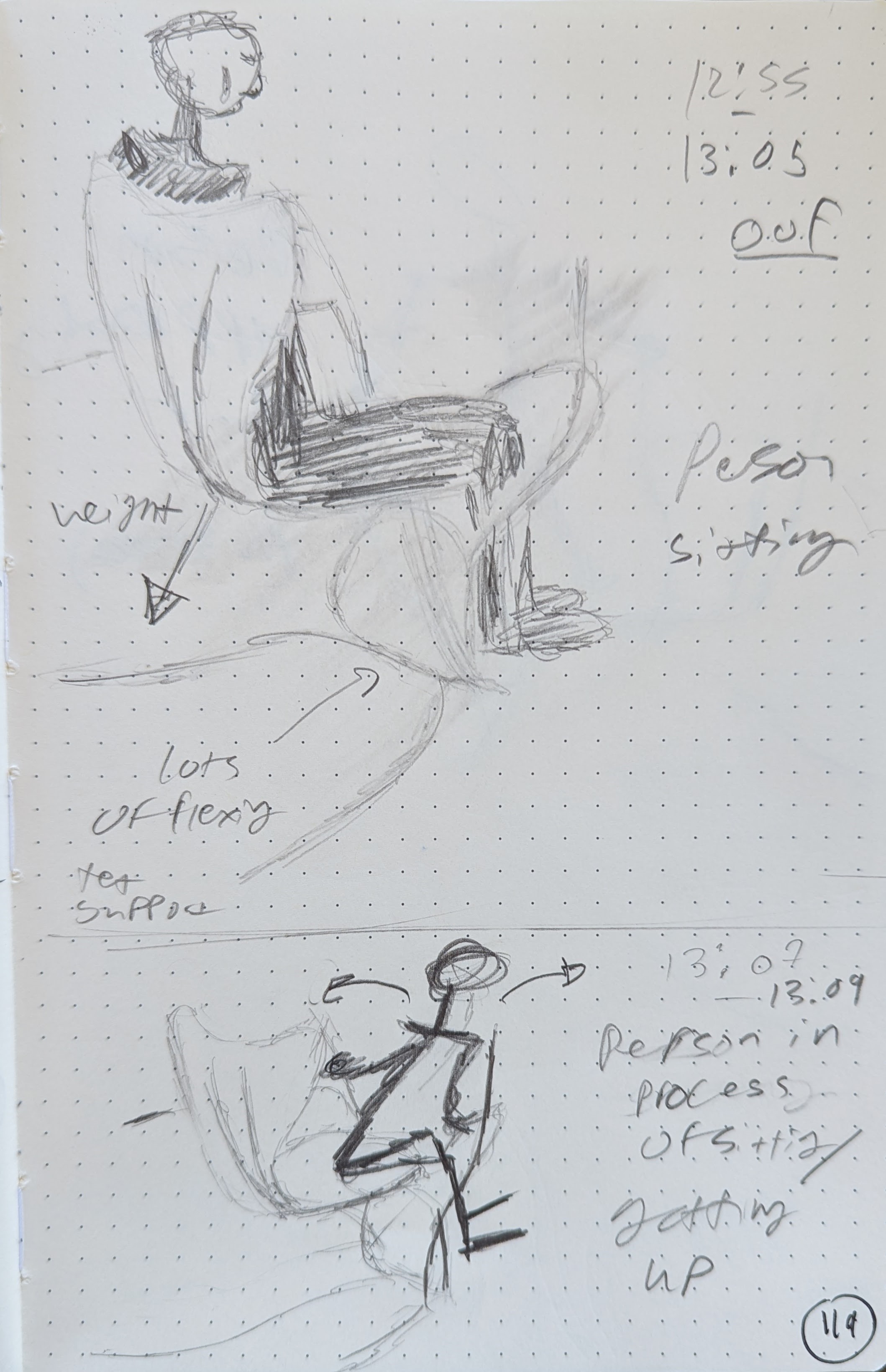

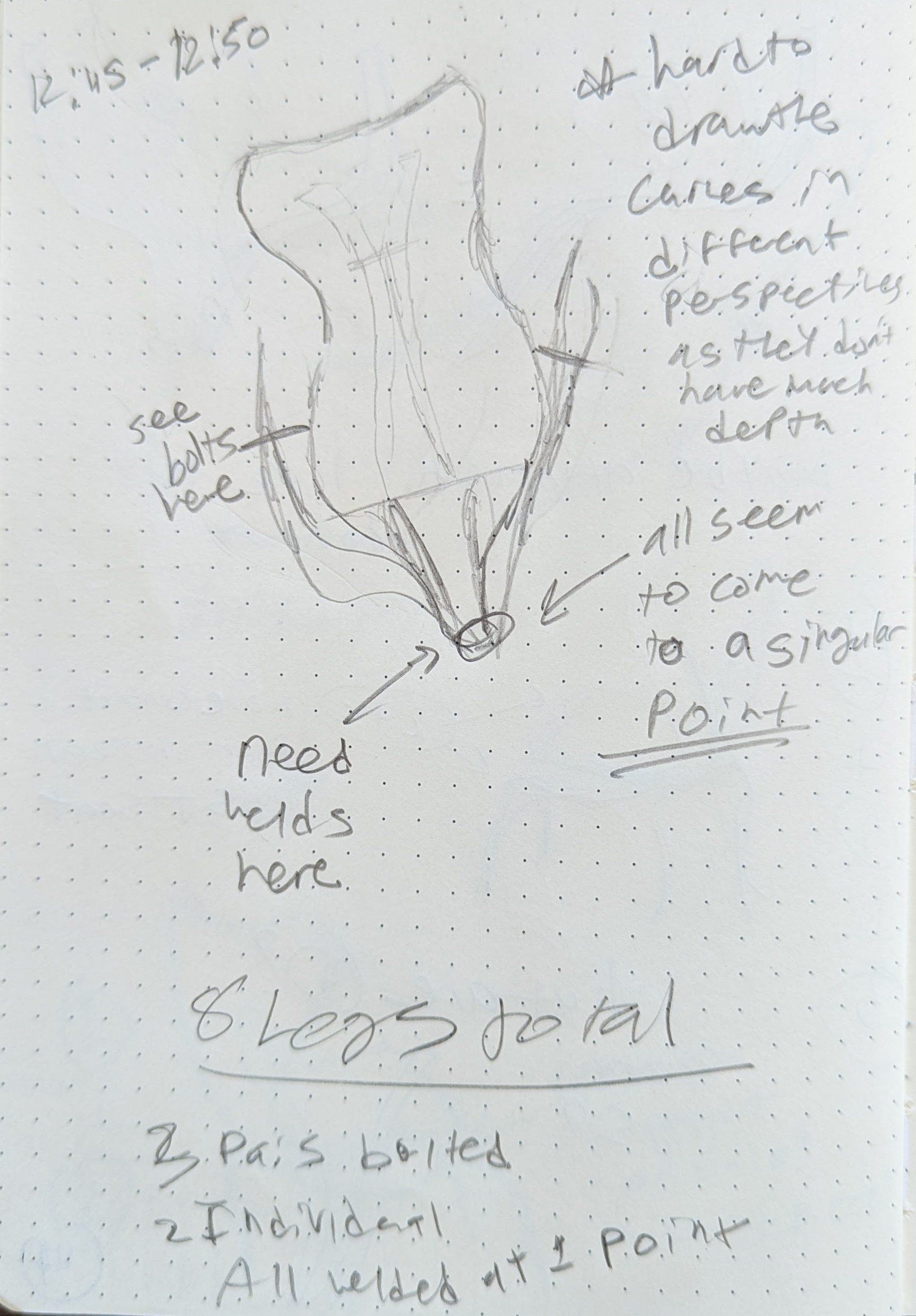

Martino Gamper’s 100 Chairs in

100 Days and Its 100 Ways

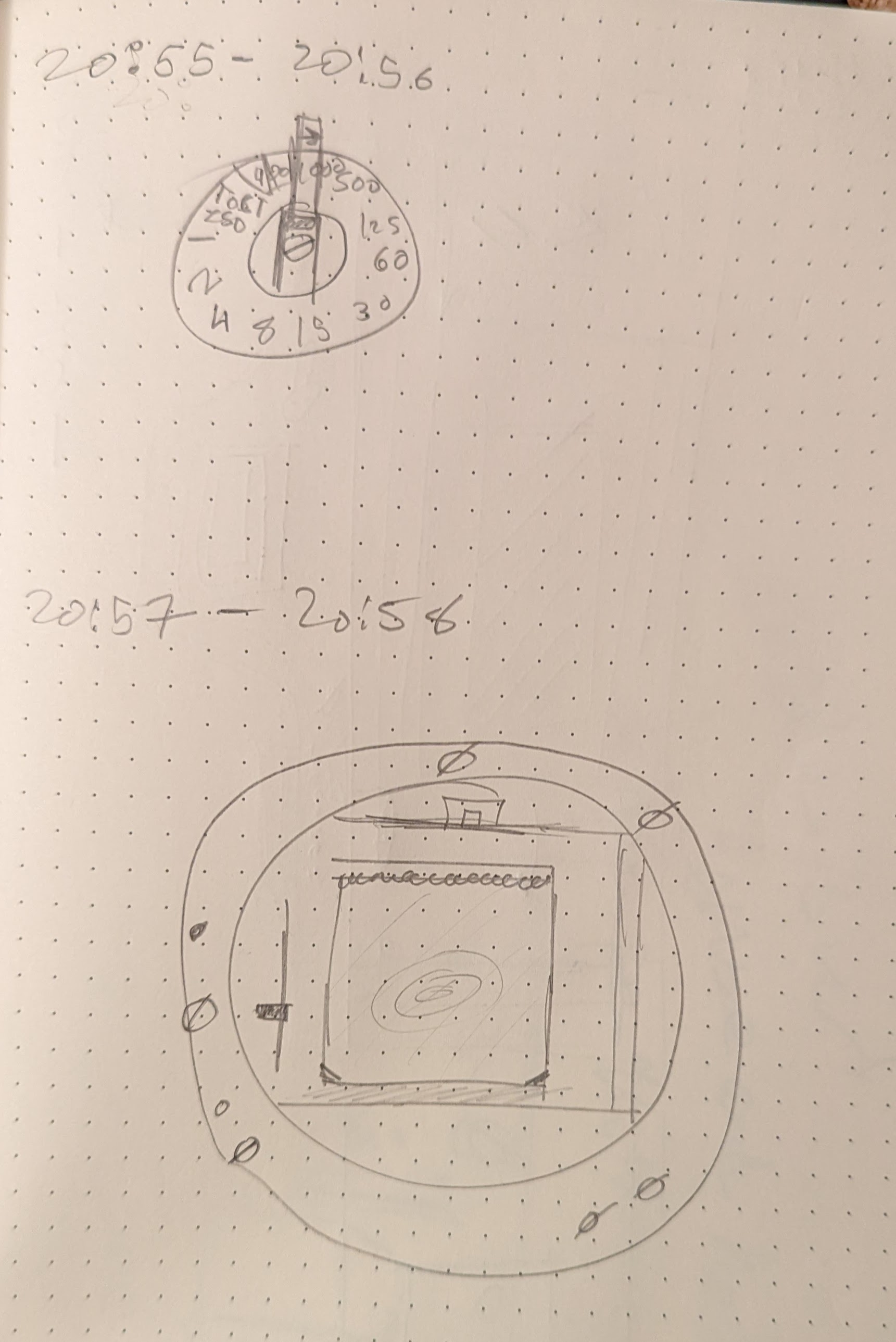

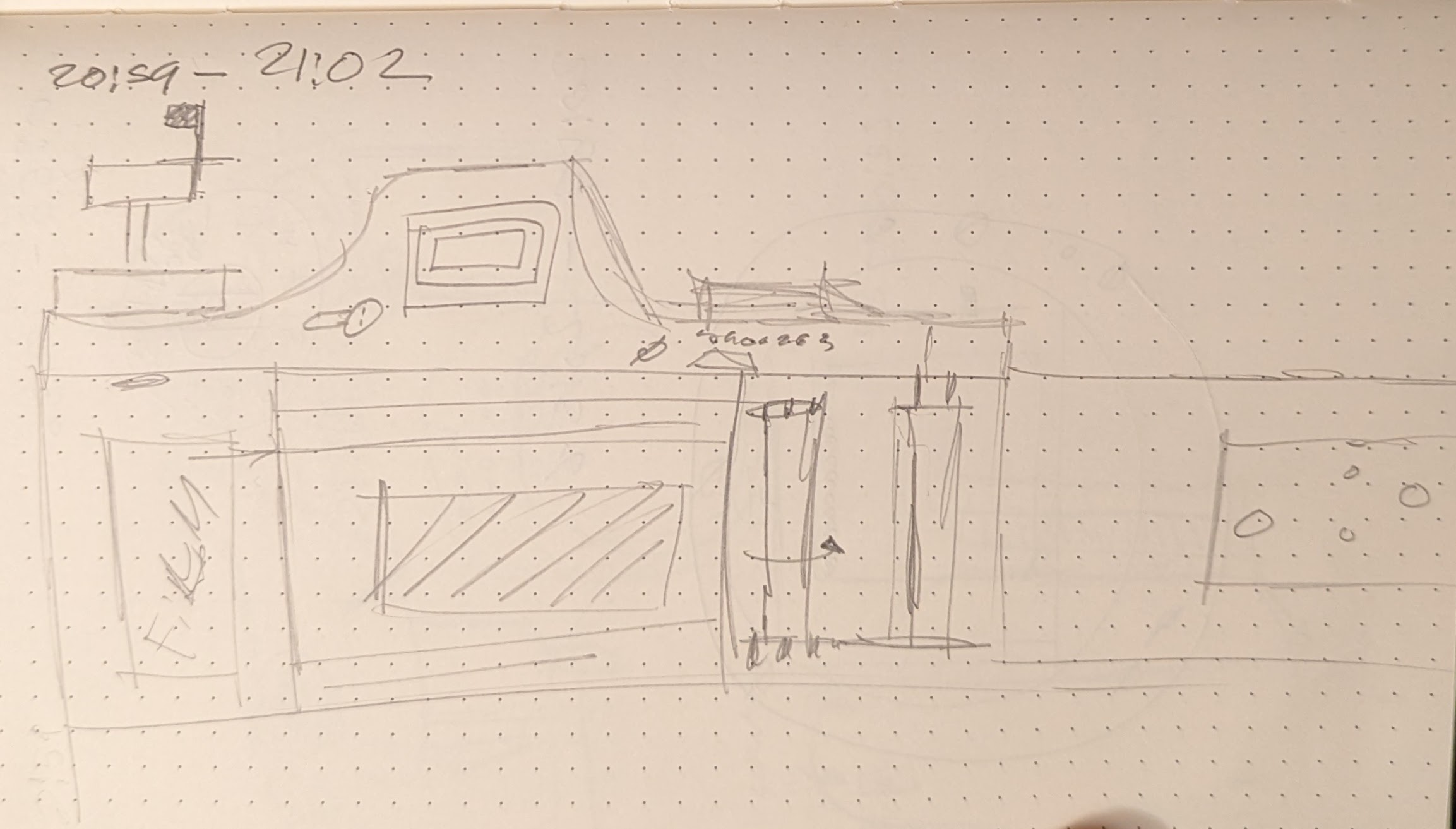

The quick sketches were then followed by diagrammatic drawings to dissect the materials and components and use case drawings that depict human-object interaction.

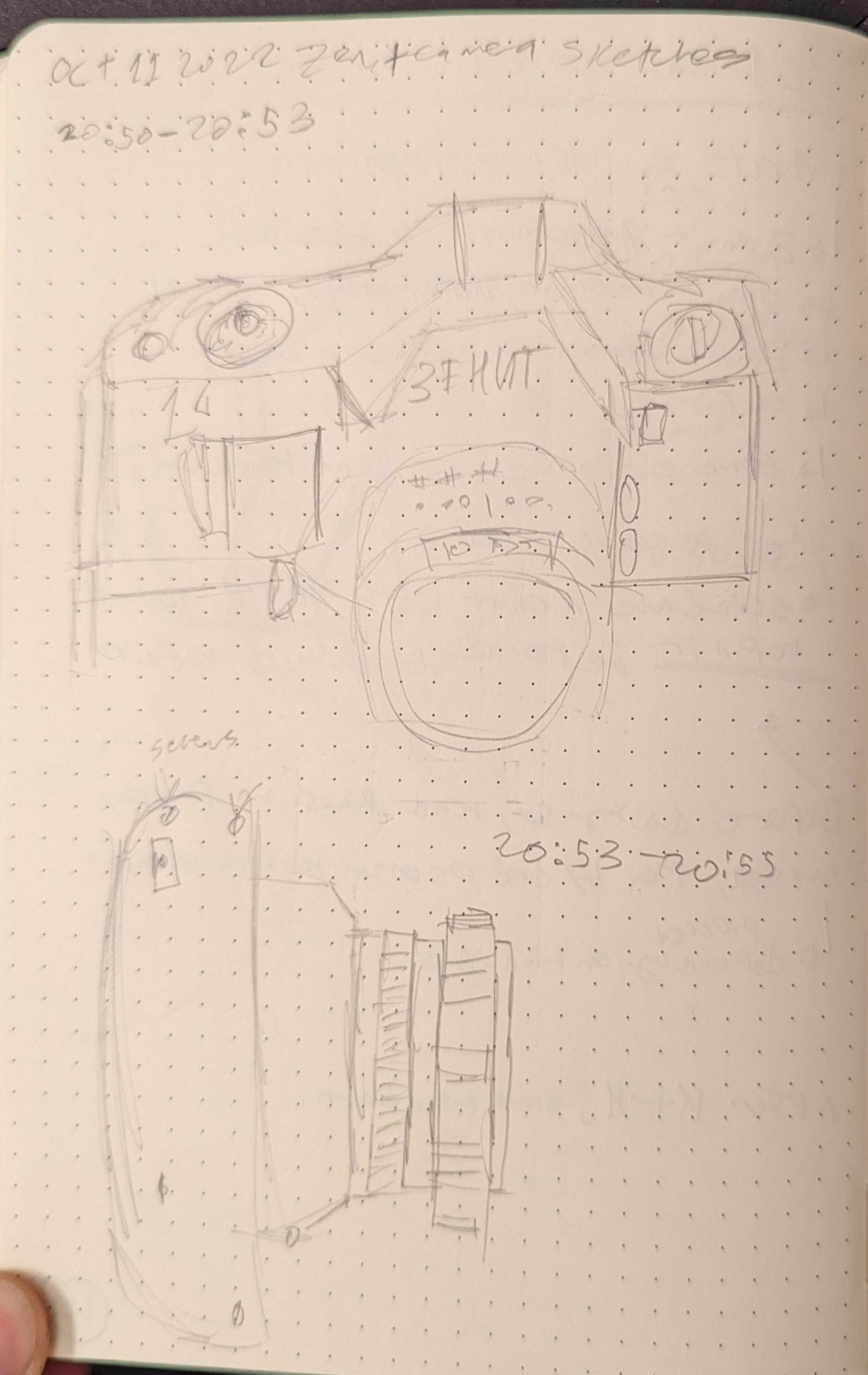

Now that I was warmed up, I sketched a few drawings of my cameras.

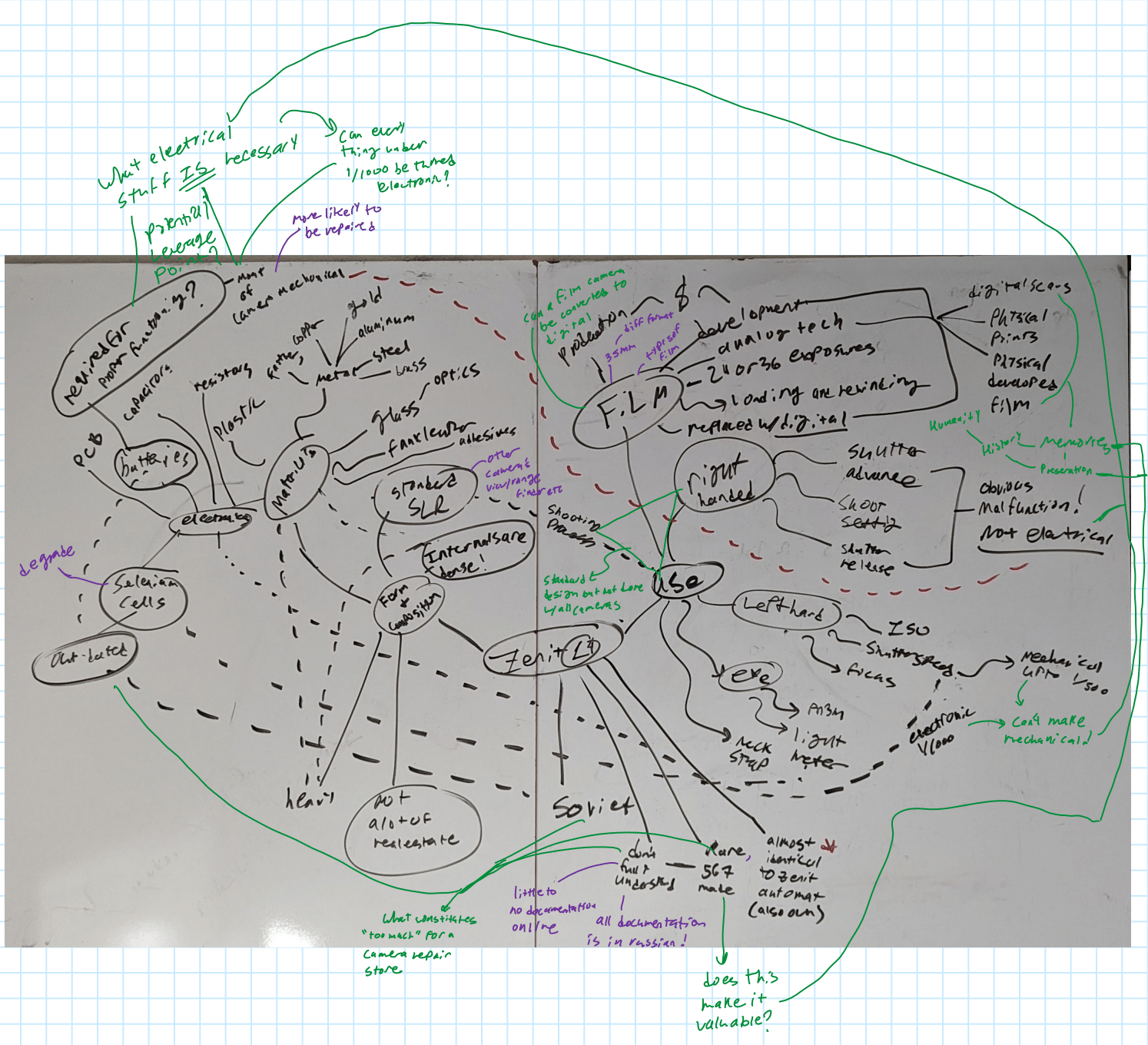

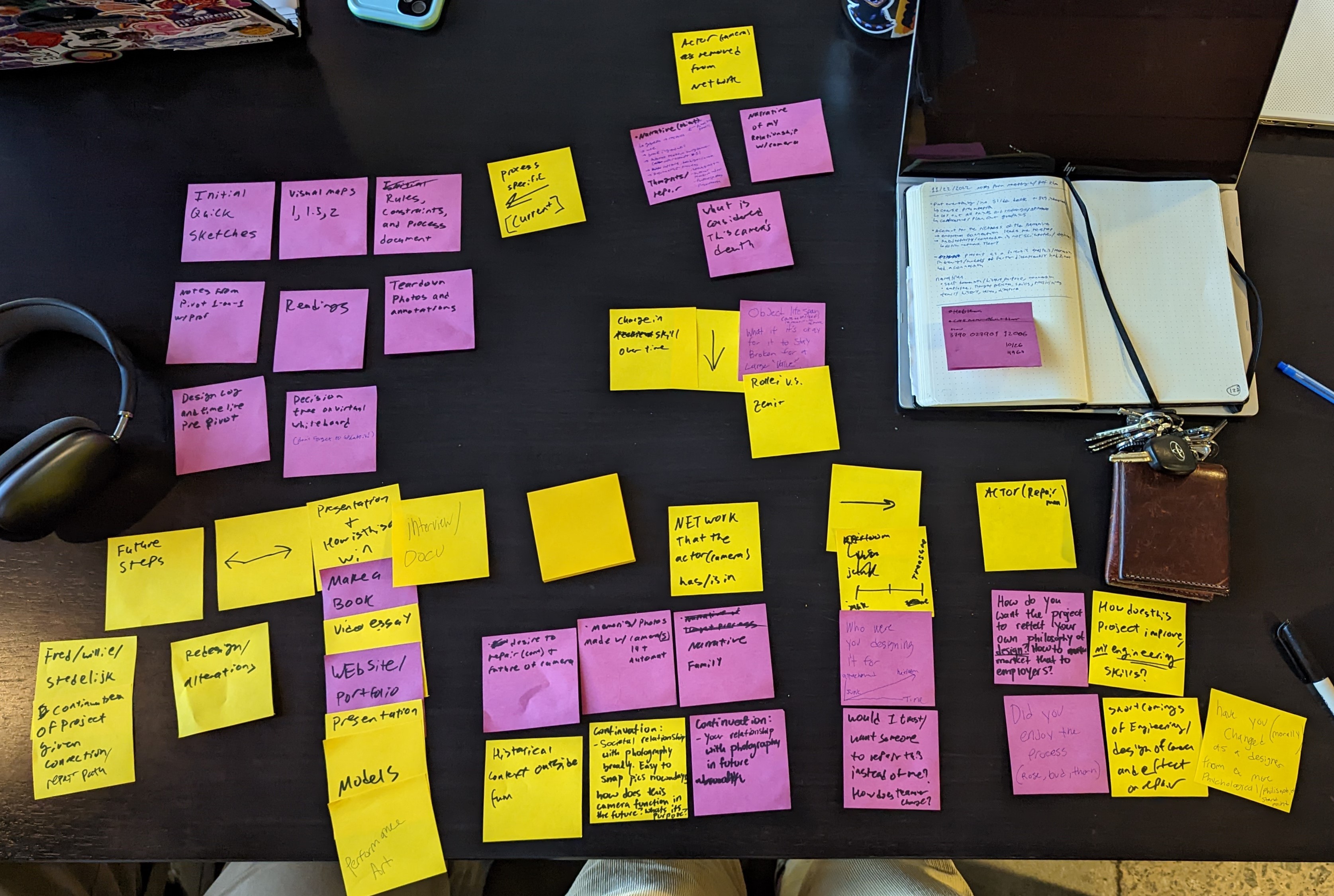

I followed up with two visual maps to help identify my problem and solution spaces and further bring my intentions and emotions toward this repair.

Discoveries and Inquiries 3: Picking an approach, process, and goals

At the end of this process, I had a greater appreciation for the camera and its journey. I realized I had a strong emotional connection to them, the Zenit 14 in particular. This exploration led to the realization that I would learn my process and motivation primarily as Fred does in Spelman’s book. I was surprised that this realization upset me, as I found Fred’s persona to be uptight, and I really enjoyed the playful and exploratory methods of Gamper, Goldstein, and Willie. Thus, I would allow myself some inspiration with the condition that the original external design philosophy of the camera developers be preserved.

Reading 4: Iteration

Luis M. Mansilla + Emilio Tunon’s From Rules to Constraints (Intro and Conversation)

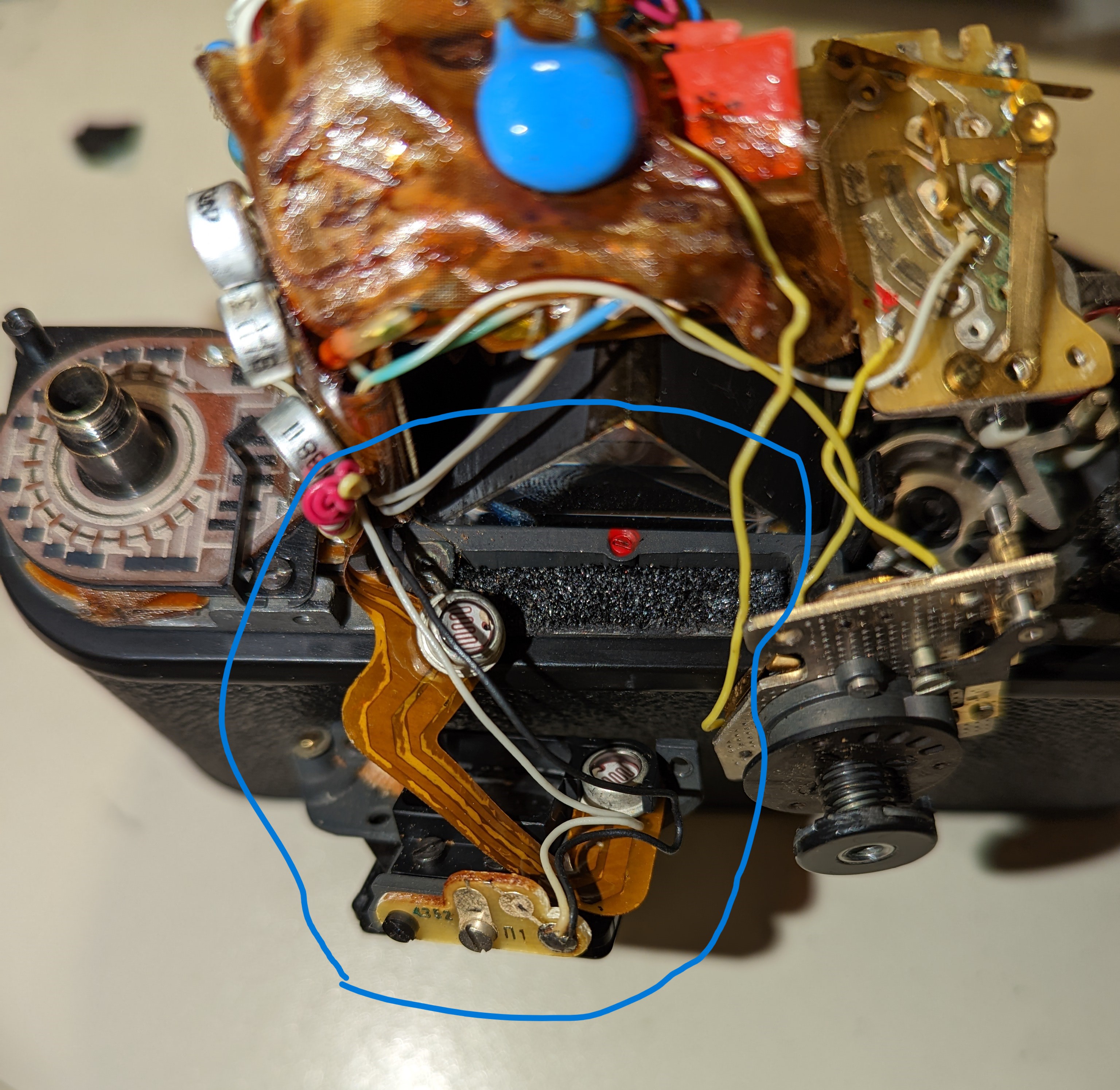

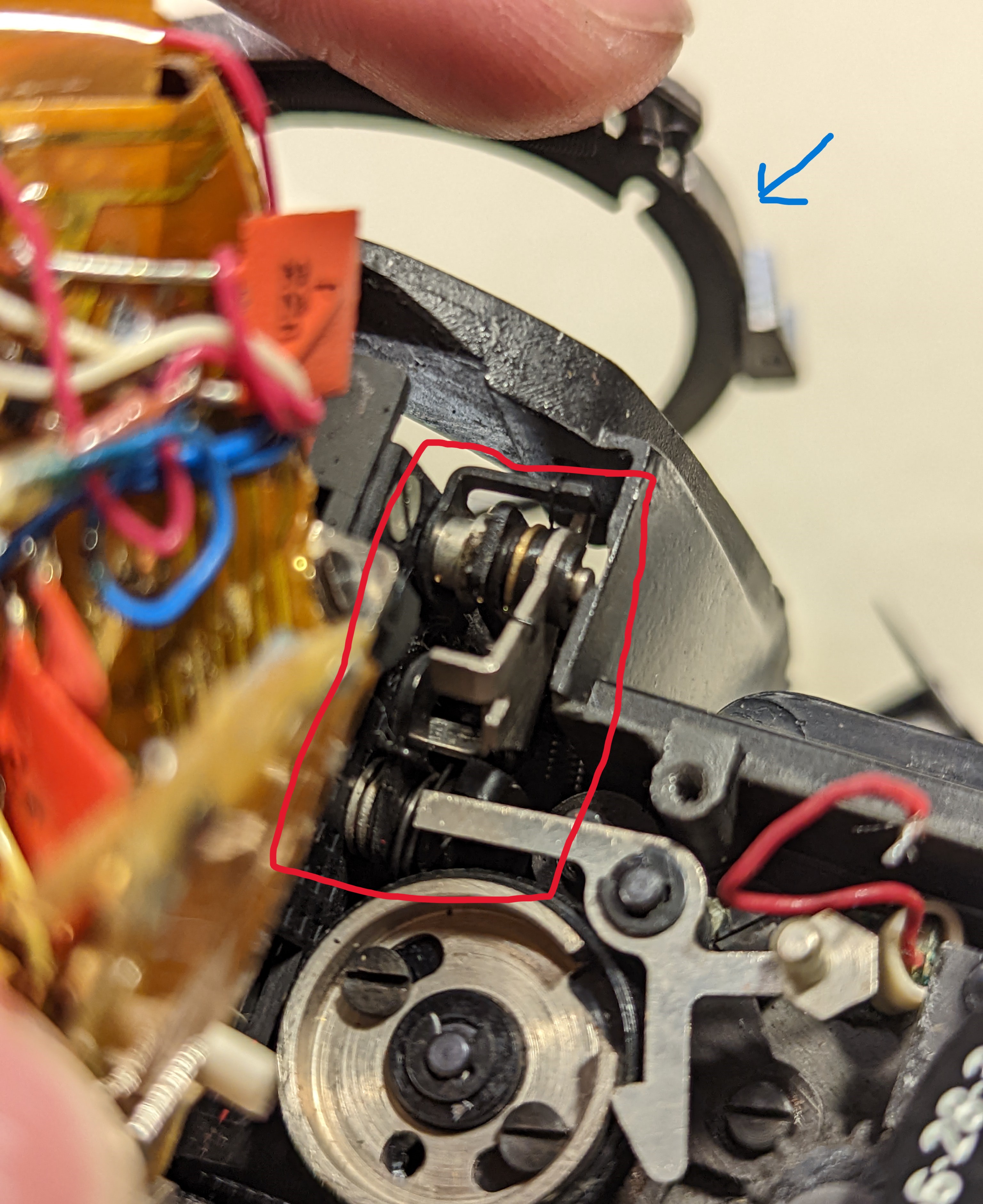

Repair 4: Further exploration - the mirror box

Discoveries and Inquiries 4: There be dragons (the mirror box)

After this discovery, I was very stressed to continue. A complete teardown would be extremely risky. I would need to deface the camera to even get to the mechanism. After consulting with my Professor Khan, he suggested. I leave the cameras as they were. We came to a consensus that the emotional connection to the cameras was important and not worth the damage.This reading came at a good time for me. I was beginning to doubt the value of the work I had done. Muecke’s eulogical piece for Bruno Latour, particularly his novel actor-network theory, helped me see a new perspective on this journey I had with my cameras. They were their own actors in my world, and they had impacted me even more than I impacted them. Thus, I tried to summarize all that I had done and what I was to do.

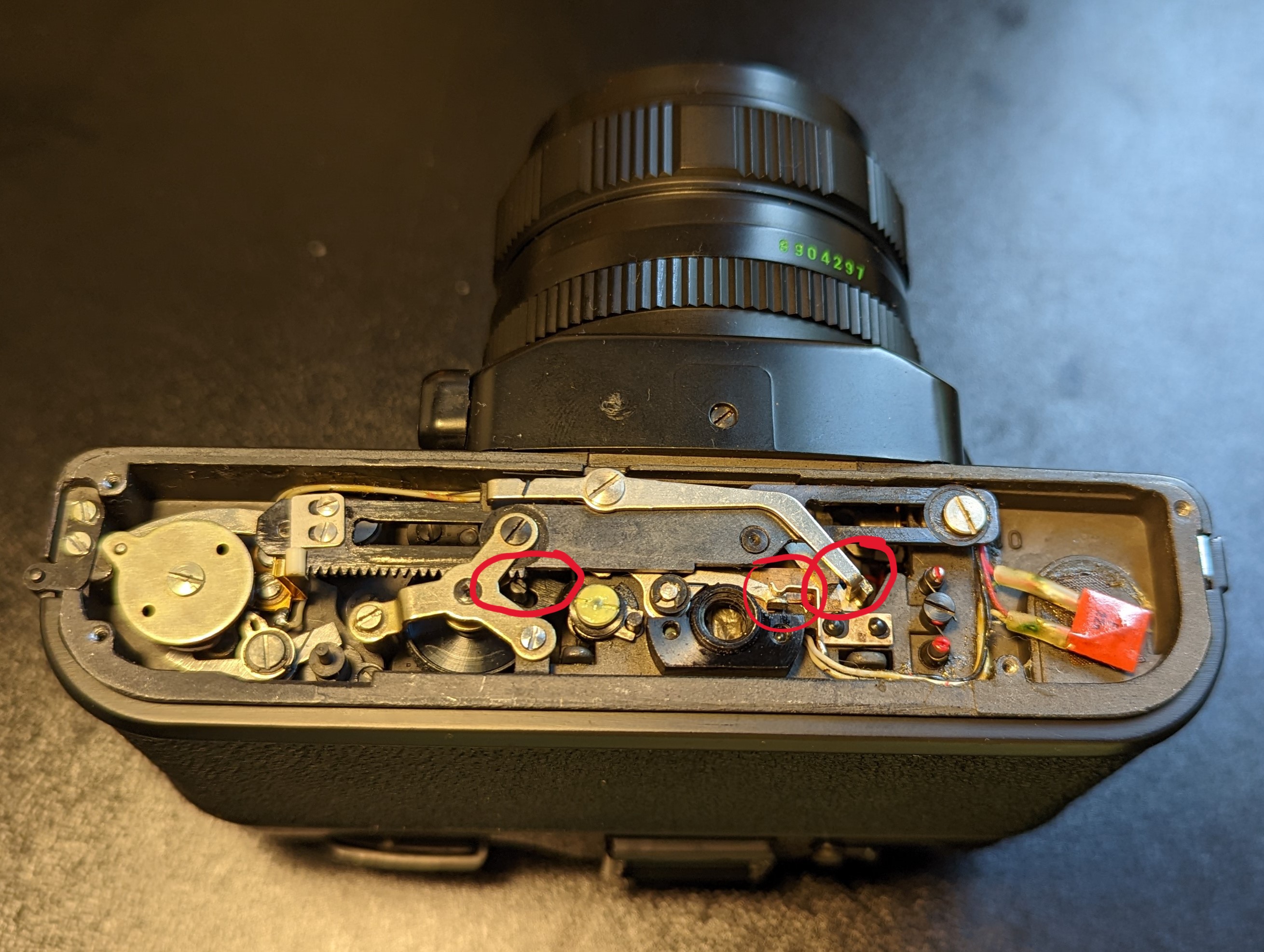

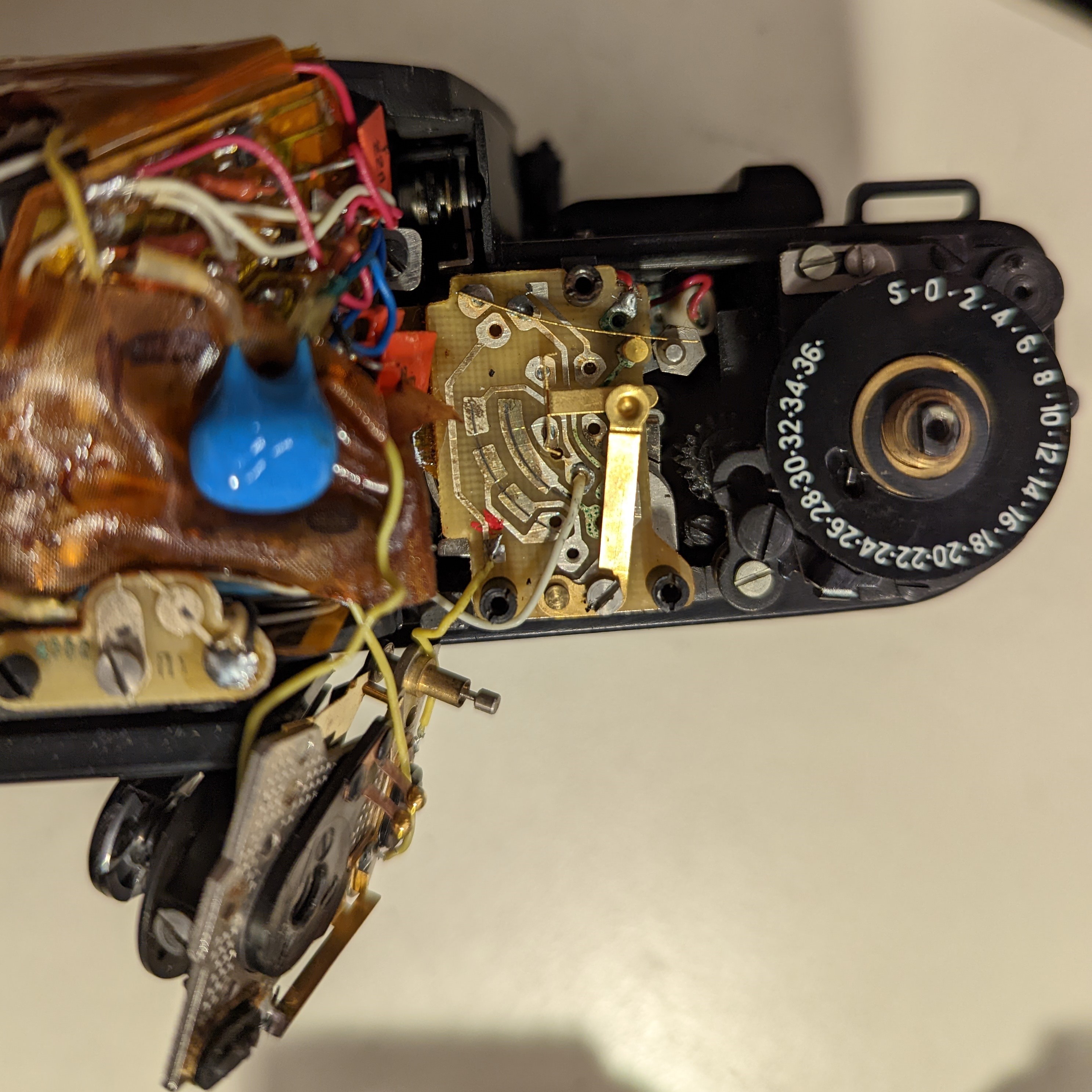

I felt as though I had to try and go further. I decided I would risk the Zenit Automat for the sake of exploration. If things went poorly, my Automat would join the Zenit 14, and if things went well then I would revive an heirloom.

Repair 5: Final restoration attempt

Discoveries and Inquiries 5: Reflections

Four hours later with the guts of the camera spilling out, I was done. I had reached a point I didn’t expect. I knew that with my current abilities there was no more I could do without causing any more irreparable damage. Once I reassembled the camera, I wound the shutter and was relieved that the Zenit Automat was still functional.

Although I was not able to repair the Zenit 14, I am content. The cameras and my attempts to repair the Zenit 14 gave me much to learn and think about. The different roles of development and operations, different motivations for design, slowing down to gain insight, the roles of rules and constraints, and finally how everything can be an actor in a world are all lessons I intend to take with me to future projects. In the meantime, the Zenit 14 serves as a beautiful artifact and and decoration. Who knows, maybe I will come back to it in the future, armed with more tools and experience, and give it a new life.